High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Accelerating Drug Discovery

Drug discovery is a search problem at massive scale: biology is complex, chemical space is enormous, and timelines are unforgiving. The challenge isn’t just finding active compounds — it’s finding reproducible, mechanism-relevant starting points fast enough to justify the next wave of chemistry and biology.

High-throughput screening (HTS) is the workhorse approach for that early decision-making. In drug discovery high-throughput screening, automated platforms test hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds against a biological target or cellular phenotype to identify “hits” worth follow-up. By combining miniaturized assays in microplates with robotics, sensitive detection, and data analytics, HTS compresses months of manual work into days to weeks and generates quantitative starting points for hit-to-lead optimization.

Why HTS matters: HTS enables standardized experimentation at scale — so teams can triage chemical matter earlier, reduce downstream attrition, and focus resources on the most promising chemotypes.

What is High-Throughput Screening?

High-throughput screening (HTS) is a systematic, automation-driven method for identifying biologically active compounds by testing very large libraries against a target (e.g., an enzyme or receptor) or a cellular phenotype. The primary goal is hit discovery: finding reproducible chemical starting points that can be optimized into leads through medicinal chemistry and iterative biology.

HTS is widely used across pharmaceutical and biotech R&D, CROs, and academic screening centers to prioritize the most promising candidates early—especially when the mechanism is well-defined (target-based screening) or when a phenotype provides the best disease-relevant readout (phenotypic screening).

In practice, HTS miniaturizes assays into microplates and uses robotics for dispensing, incubation, and detection. Software then normalizes results, applies quality-control statistics (e.g., Z′), and flags “hits” for confirmation, orthogonal testing, and early structure–activity relationship (SAR) learning.

Related technologies: DNA-Encoded Library Screening

A Brief History of HTS

Since the emergence of HTS in the early 1990s, the screening collections have grown from 50-100,000 compounds to several million today (TheScientist 2024). Screening compound collections of this size is challenging, and efficient automation and organization are essential for successful HTS campaigns.

The integration of robotics, miniaturization, and powerful data analytics tools has made HTS a staple in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D), particularly among organizations aiming to achieve high-efficiency lead generation while minimizing resource expenditure.

A typical HTS campaign, from target validation to hit confirmation, can take anywhere from several weeks to a few months, depending on the complexity of the assay, the size of the compound library, and the level of automation employed. In well-established platforms, timelines as short as 4–6 weeks from assay readiness to hit confirmation are possible.

How HTS Works: Core Concepts and Workflow

Figure 1: Overview of the HTS workflow

Core concepts in HTS

Compound libraries provide the chemical diversity to discover new starting points. Targets define what “activity” means biologically. Assays translate biology into a measurable signal, and hit identification/validation separates true actives from artifacts using confirmation, orthogonal methods, and early SAR.

Step-by-step HTS workflow

1) Target selection and validation

Targets are chosen based on disease relevance, druggability, and feasibility of building a robust assay. Validation typically combines genetic/clinical evidence, pathway context, and tool molecules or reference ligands to confirm that modulating the target produces a meaningful biological effect.

2) Assay development and optimization

Assay design defines the readout (biochemical vs. cell-based, endpoint vs. kinetic) and the detection modality (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence). Optimization focuses on robustness and scalability: selecting controls, confirming DMSO tolerance, minimizing edge effects, and tuning conditions to achieve strong signal windows. Screening teams commonly track assay performance with metrics like Z′-factor, signal-to-background, and coefficient of variation. Z′-factor is a standard robustness metric in HTS; values closer to 1 indicate better separation between positive and negative controls (often ≥0.5 is considered excellent for screening, Zhang 1999).

3) Compound library selection and management

Libraries may be diverse (“discovery”) or target-focused (e.g., kinase sets, covalent fragments, CNS subsets). Practical success depends on logistics: compound identity/purity verification, solubility and stability in DMSO, barcoding/plate maps, storage conditions, and “cherry-pick” traceability for follow-up testing.

4) Plate setup and compound dispensing

Compounds are formatted into assay-ready plates (often 384- or 1536-well) using acoustic dispensing, pin tools, or automated pipetting. Plate design includes controls, replicates, and sometimes concentration series. Sealing, humidity control, and standardized timing reduce evaporation-driven artifacts.

5) Primary screen execution

Automation coordinates dispensing, incubation, and readout across thousands of wells with minimal human intervention. Environmental consistency (temperature, CO₂ for cells, incubation times) and batch monitoring are critical to reduce drift and improve reproducibility.

6) Data acquisition and processing

Detection instruments generate raw signals that are normalized to controls, quality-checked, and transformed into activity scores. Pipelines flag outliers, compute plate QC, and apply hit-calling thresholds (often followed by curve fitting when concentration-response data are available).

7) Hit confirmation and prioritization

Putative hits are retested (often from fresh material) to confirm reproducibility, followed by dose–response curves to estimate potency. Orthogonal assays and counterscreens help eliminate detection interference, aggregation, and non-specific toxicity. Confirmed hits are prioritized using early SAR, selectivity profiling, and preliminary developability checks (e.g., solubility, stability, basic ADME flags). Because primary-screen hit rates are often well under 1% (and sometimes far lower), confirmation and orthogonal validation are essential to avoid chasing artifacts.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the high-throughput screening (HTS) workflow: target selection and validation → assay development and optimization → compound library selection and management → plate setup and compound dispensing → automated primary screening → data processing and hit calling → hit confirmation and validation, with iteration back to assay optimization.

Key Technology & Instrumentation

HTS platforms combine miniaturized assay formats with automation and high-sensitivity detection. While exact setups vary by assay type, most screening centers rely on the same core technology stack:

Microplates and miniaturization

Modern HTS typically uses 96-, 384- and 1536-well plates (with specialized formats for ultra-miniaturization). Smaller volumes reduce reagent cost per data point and increase throughput, but demand tighter control of evaporation, mixing, and timing.

Liquid handling and dispensing systems

Automation starts with accurate dosing: tip-based liquid handlers, bulk dispensers for reagents, and low-volume tools (e.g., acoustic dispensing or pin tools) for transferring compounds. These systems standardize timing and reduce variability compared to manual pipetting.

Plate readers and detection modalities

Readout choice determines which instrument you need and what artifacts to watch for. Common modes include:

-

- Fluorescence intensity (FI): sensitive, widely used for binding and enzymatic assays.

- Luminescence (LUM): high sensitivity with low background (often luciferase-based).

- Absorbance (ABS): straightforward optical density measurements for many enzyme reactions.

- FRET / TR-FRET: proximity-based fluorescence; TR-FRET reduces background by time-gating.

- BRET: proximity readout driven by bioluminescence rather than excitation light.

- AlphaScreen/AlphaLISA: bead-based proximity assays that work well for difficult targets.

Automation platforms and environmental control

Integrated systems may include robotic arms, plate stackers/carousels, incubators (temperature/CO₂/humidity), sealers/peelers, and scheduling software to run assays consistently—often around the clock.

High-content screening (HCS) systems

High-content screening (HCS) is often considered a subset/adjacent approach to HTS: instead of a single signal per well, HCS uses automated microscopy and image analysis to quantify multi-parameter cellular phenotypes (e.g., morphology, localization, pathway markers). HCS is especially valuable for complex biology, but typically increases data volume and analysis complexity.

HTS vs. HCS (high-content screening): HTS and HCS share automation and microplate workflows, but they differ in readout complexity and analysis burden.

| Feature | HTS | HCS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary readout | One signal per well (e.g. FI, LUM, ABS) | Image-based, multi-parameter cellular features |

| Typical use | Rapid hit finding in large scale | Mechanism- and phenotype-rich screening, complex biology |

| Data volume | High | Very high (data-heavy) |

| Analysis | Statistics and curve fitting | Computer vision and ML-based feature extraction |

| Strength | Throughput + cost per datapoint | Physiological relevance and rich biology |

Informatics (LIMS/ELN) and data analysis software

Because HTS produces large, plate-structured datasets, informatics is not optional. LIMS/ELN tools track sample provenance, plate maps, concentrations, and QC metrics across runs. Analytics pipelines handle normalization, curve fitting, outlier detection, hit calling, and reporting—enabling faster triage and more reproducible decision-making.

Compound Libraries in HTS: Design, Synthesis, and Management

The success of an HTS campaign depends as much on the library as the assay. Libraries can be built in-house or sourced commercially, and are typically curated to balance chemical diversity, developability, and screening robustness.

Libraries are either generated by in-house laboratories or by purchasing commercially available compound collections. A high-quality chemical library will have the following features:

- Chemical diversity & coverage: Broad scaffold and shape diversity (including 3D-rich/ sp³ content) to maximize novel chemotypes while maintaining clusters of close analogs for rapid SAR.

- Drug-like property profile: Filtered for desirable ranges (e.g., MW, clogP, HBD/HBA, TPSA) tailored to the target class; include subsets (fragment-, lead-, and probe-like).

- Quality & identity control: Verified purity/identity (LC-MS/NMR), low salts/residual reagents, and robust metadata (SMILES, stereochemistry, batch history).

- Liability filtering: Removal of PAINS, frequent hitters, redox cyclers, covalent/reactive moieties (unless intentional), chelators, and aggregators; include counterscreen flags.

- Solubility & stability: DMSO compatibility, precipitation checks, controlled water content, and policies to minimize freeze–thaw cycles; stability monitoring over time.

- IP and novelty: Preference for synthetically accessible, novel scaffolds with freedom-to-operate and avenues for follow-up chemistry.

- Biology-aware subsets: Target-class or modality-enriched panels (kinase-focused, PPI, CNS-penetrant, covalent warheads) to boost hit relevance.

- Automation-ready formatting: Standardized plate formats (384/1536), barcoding, tracked concentrations/volumes, and plate maps with control wells.

- Data & logistics: LIMS integration, cherry-pickability, replenishment strategies, and provenance auditing—crucial for reproducibility and scale.

Library synthesis and evolution: Many modern HTS collections are built using combinatorial and diversity-oriented synthesis to generate broad scaffold coverage at scale. Key challenges include maintaining purity and identity across thousands of compounds, increasing 3D/sp³-rich diversity (to avoid overly “flat” chemical space), and ensuring compounds remain soluble and stable during storage and repeated handling. As a result, many organizations pair experimental curation with computational design to target underrepresented regions of chemical space while preserving tractable follow-up chemistry.

Despite the scalability of this method, there are significant challenges:

- Achieving High Purity: With automated synthesis and scale, maintaining consistent purity across thousands of compounds is difficult. Impurities can interfere with assay results and lead to false positives or negatives.

- 3D Diversity and Stereochemistry: Traditional combinatorial libraries often result in flat, aromatic-rich compounds. There is a growing emphasis on incorporating 3D structural diversity to better mimic natural ligands, improve bioavailability, and reduce attrition rates.

- Novel Scaffolds: Generating libraries with novel scaffolds, rather than just variations on known drugs, remains a key challenge to unlock unexplored chemical space.

- Cost and Logistics: Synthesizing, validating, storing, and reformatting HTS libraries for screening can be costly and logistically intensive, especially for startups with limited infrastructure.

To address these issues, some companies are turning to diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) and leveraging AI-driven library design tools to predict and prioritize structurally and functionally rich chemical spaces.

HTS Across the Drug Discovery Pipeline

HTS contributes across multiple phases of discovery — from confirming target biology to generating and refining lead series. In practice, teams use HTS screening differently depending on where they are in the pipeline:

1) Target identification and validation

HTS can support target validation by testing tool compounds, reference ligands, or focused libraries to confirm that modulating a target produces the expected biological effect. In phenotypic settings, screening can also help connect pathway perturbations to actionable targets through follow-up deconvolution.

2) Lead discovery and hit identification

This is HTS’s primary role: running large-scale small molecule screening to identify initial “hits” from diverse or target-focused libraries, followed by confirmation and orthogonal assays to remove artifacts.

3) Lead optimization and SAR development

After hits are confirmed, iterative screening of close analogs (often in dose–response format) accelerates structure–activity relationship (SAR) learning. Secondary and counterscreen panels are used to improve potency, selectivity, and developability while reducing false-positive mechanisms.

Applications in Drug Discovery

HTS is used in a wide range of discovery applications, including:

- Hit identification: Primary screens reveal active compounds against a biological target.

- Lead optimization: Iterative screening of compound analogs refines efficacy, potency, and ADMET properties.

- Target deconvolution: In phenotypic screens, HTS helps elucidate the mechanism of action of active compounds.

- Mechanistic studies and pathway profiling: HTS enables systematic study of compound effects on signaling pathways or gene expression.

- Functional genomics: Identifying genes that play roles in specific pathways and understanding gene functions.

- Toxicology: Identifying potential toxicity of entire compound libraries.

HTS provides a competitive advantage by enabling rapid hypothesis testing, reducing time-to-discovery, and enhancing the quality of candidate selection. By leveraging public HTS data repositories like PubChem BioAssay, smaller firms can also validate in-house findings or expand SAR understanding.

Real-world example of HTS success

A classic HTS success is ivacaftor (VX-770) for cystic fibrosis. Vertex screened ~228,000 small molecules in a cell-based fluorescence assay to find CFTR “potentiators,” then optimized hits into VX-770, which increased CFTR channel open probability and restored chloride transport in vitro. Clinical studies confirmed benefit for patients with gating mutations (e.g., G551D), leading to the first CFTR-modulator approval in 2012. This path—from HTS hit to approved precision therapy—is documented in primary papers and regulatory/web sources (Van Goor 2009, Vertex 2012).

Advantages and Benefits of High-Throughput Screening

When assays are well-optimized and libraries are well-curated, HTS offers several practical advantages in early discovery:

- Speed and efficiency: rapidly tests large libraries to identify starting points earlier in the pipeline.

- Lower cost per data point: miniaturization and automation reduce reagent use and per-well labor.

- Access to novel chemical starting points: diverse libraries increase the chance of finding new chemotypes.

- Reduced manual labor and improved reproducibility: standardized automation reduces human error and variability.

Better prioritization under uncertainty: quantitative screening + early SAR improves decision-making before expensive in vivo work.

Challenges and Limitations of High Throughput Screening

HTS trades depth-per-experiment for breadth and standardization. The most common pitfalls fall into assay artifacts, data complexity, operational cost, and library representativeness—so successful campaigns plan for triage and validation from day one.

False positives, false negatives, and assay artifacts

Data Overload and Interpretation

A single campaign can generate millions of datapoints across plates, replicates, timepoints, and conditions—especially when imaging or multi-parameter readouts are used. Without standardized normalization, plate/QC monitoring, and reproducible pipelines for hit calling and curve fitting, teams can either miss real actives (over-filtering) or chase noise (under-filtering). This is why HTS groups invest heavily in informatics, statistical QC, and clear triage criteria before screening begins.

High initial setup cost and operational complexity

HTS requires significant upfront investment in robotics, detection hardware, environmental control, and trained staff. Even when the per-well cost is low, the platform-level cost can be a barrier for smaller teams—driving interest in partnerships, CRO models, or complementary approaches like DEL or virtual screening.

Limited biological context

Limited chemical diversity (in some libraries)

Quality Control Measures

Quality control (QC) safeguards the credibility of high-throughput screening data; without it, projects burn time and budget chasing artifacts. QC typically spans two buckets: plate-based and sample-based controls. Plate-based controls assess how each plate performs and flag assay problems—think pipetting mistakes or “edge effects” from evaporation at perimeter wells. Sample-based controls track variability in biological response or compound potency across runs. A common metric is the minimum significant ratio (MSR), which quantifies assay reproducibility and the degree to which control or sample potencies differ between experiments.

PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds)

A persistent challenge in HTS is the presence of pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS). These are compounds that produce false positives across multiple assay types due to their chemical reactivity, aggregation, redox activity, or interference with assay detection mechanisms (Baell 2018). PAINS can skew screening results, misdirect follow-up efforts, and waste valuable resources.

Identifying and filtering out PAINS early in the screening process is crucial. Computational filters and curated substructure databases are used to flag known PAINS motifs. However, these tools are not foolproof, and careful experimental validation remains necessary. Companies must balance the risk of excluding potentially valuable compounds with the need to eliminate confounders that undermine screening fidelity.

Educating screening scientists and medicinal chemists about PAINS and investing in robust triaging strategies can dramatically improve hit quality and downstream success rates.

Alternative Screening Approaches:

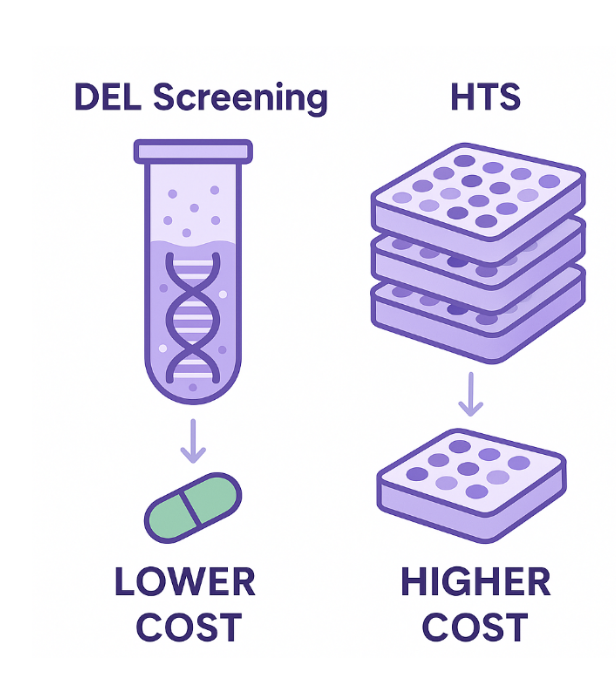

DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) Screening

DEL technology allows the screening of billions of compounds by tagging each with a DNA barcode, enabling solution-phase binding assays and rapid hit identification. One of the major advantages of DEL is its significantly lower cost compared to HTS, both in terms of library acquisition and operational expenses. DEL libraries can be synthesized or accessed through partnerships at a fraction of the cost of traditional HTS libraries. Moreover, DEL screening is conducted in a single reaction tube, eliminating the need for hundreds or thousands of microtiter plates, complex automation, and high-throughput robotics. This makes the overall setup far simpler and more accessible for e.g. small biotech firms or early-stage discovery labs.

- Screens billions of DNA-barcoded compounds in solution-phase binding selections

- Lower cost per “virtual compound” compared with plate-based HTS

- Requires off-DNA resynthesis + follow-up functional assays to confirm activity

- Best for: fast binder discovery, very large chemical space exploration

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD)

FBDD involves screening low molecular weight compounds— “fragments”—that bind to a target with weak affinity but high specificity. Though individually less potent than typical HTS hits, these fragments serve as efficient starting points for lead optimization. Detection typically requires sensitive biophysical techniques such as NMR spectroscopy, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), or X-ray crystallography. A key advantage of FBDD is its efficiency: smaller libraries (often in the range of hundreds to a few thousand compounds) can yield highly novel chemical matter with desirable drug-like properties.

Virtual Screening

Phenotypic Screening

Integration with Multi-Omics and Systems Biology

As the complexity of therapeutic targets grows, the integration of high-throughput screening with multi-omics approaches (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) offers a more comprehensive understanding of drug-target interactions and downstream effects. By mapping screening hits to omics datasets, researchers can:

- Identify off-target activities or biomarkers associated with compound response

- Elucidate the mechanism of action with greater precision

- Predict efficacy across patient subtypes using systems biology models

Moreover, combining HTS results with transcriptomic or proteomic data can uncover pathway-level perturbations and reveal synergistic interactions in polypharmacology approaches. This integrative strategy not only supports more informed hit prioritization but also aligns with precision medicine objectives (Meissner 2022).

Future Trends in High-Throughput Drug Discovery

HTS is evolving beyond “faster plates” into smarter experimentation — combining automation, richer biology, and predictive analytics to reduce false positives, de-risk hits earlier, and prioritize chemistry that is more likely to translate.

Integration with AI and machine learning

AI is increasingly used to improve HTS decision-making at multiple points: identifying assay interferents, improving hit calling, prioritizing which hits to retest first, and predicting which chemotypes are most likely to survive follow-up validation. In more advanced workflows, active-learning loops can propose the next set of compounds to test, accelerating SAR development while reducing the number of experiments needed (Boldini 2024).

Miniaturization and ultra-HTS (microfluidics, picoliter volumes)

Traditional HTS relies on 384–1536 well plates, but ultra-HTS pushes miniaturization into microfluidic droplets that act like tiny reaction vessels (often pico- to nanoliter volumes). These approaches can massively increase throughput and reduce reagent costs, while enabling single-cell or rare-event assays that are hard to run in plates (Yang 2025, Das 2025).

Organ-on-a-chip, organoids, and 3D cell cultures

More physiologically relevant models — including organoids, 3D cultures, and high-throughput organ-on-a-chip (OoC) systems — are being integrated into screening to improve translatability. These platforms aim to bridge the gap between simplified in vitro assays and in vivo outcomes by capturing tissue-level behavior (e.g., barrier function, flow, multicellular interactions) in scalable formats (Song 2024, Leung 2022).

Label-free screening technologies

Label-free approaches reduce dependence on fluorescent or luminescent reporters and can provide more direct biochemical readouts. Two areas gaining momentum are:

- Biosensors (optical/electrochemical/piezoelectric) for real-time binding and kinetic measurements (Chieng 2024).

- Mass spectrometry–based screening (e.g., rapid injection or acoustic ejection MS) that can quantify substrates/products without labels and can reduce assay artifacts linked to reporters (Smith 2025, Winter, 2023).

Phenotypic screening revival powered by high-content screening

Phenotypic screening is resurging as imaging, automation, and analysis improve. High-content screening (HCS) enables multi-parameter cellular profiling at scale, and modern image analysis (often ML-assisted) helps teams connect phenotypes to mechanisms and prioritize hits with stronger biological relevance (Seal 2024, Subramani 2024).

Quantum computing (longer-term potential)

Quantum computing is still early for most discovery teams, but it may eventually impact drug discovery through faster molecular simulation and quantum machine learning approaches for high-dimensional prediction tasks. Near term, it is best viewed as an emerging capability rather than a standard HTS tool (Danishuddin 2025, Banait 2025).

Conclusion

High-throughput screening remains one of the fastest ways to turn biological hypotheses into validated chemical starting points — especially when assay quality, library design, automation, and data triage are engineered as a single workflow. As HTS evolves toward AI-assisted analytics, ultra-miniaturization, label-free readouts, and more physiologically relevant models (3D systems and organ-on-a-chip), the winners will be the teams that can generate clean hits and learn reliable SAR quickly.

Vipergen supports discovery teams with scalable screening strategies utilizing the complementary approach of DNA-encoded library (DEL) screening, helping reduce uncertainty early and accelerate the path from target to lead. If you’re planning a screening campaign, consider aligning assay design, library strategy, and confirmation methods upfront to maximize signal quality and downstream success.

FAQ

HTS compresses many small, well-controlled experiments into microplates (typically 384–1536 wells) so thousands to millions of compounds can be tested quickly. Assay mixes (enzyme, cell, or target) are dispensed with controls, compounds are added, and automated readers quantify responses (fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance, imaging). Robust statistics (e.g., Z’-factor) ensure assay quality, while normalization and hit-calling thresholds flag “actives.” Follow-up steps include hit confirmation (retakes, counterscreens), dose–response curve fitting, and orthogonal/biophysical validation to weed out artifacts and enrich true, mechanism-relevant starting points for medicinal chemistry.

HTS evaluates discrete, physical compounds one well at a time, directly observing assay responses; it excels when you need quantitative pharmacology (potency, efficacy) early and when cell-based phenotypes or complex readouts matter. DNA-encoded library (DEL) screening binds ultra-large, DNA-barcoded mixtures to a target, washes away non-binders, and identifies enriched chemotypes by DNA sequencing. DEL campaigns are typically faster and cheaper per compound and explore far larger chemical space but primarily report binders requiring off-DNA resynthesis and follow-up assays. For an overview, see Vipergen’s technology page

Glossary of HTS Terms

- Z′-factor (Z-prime): Assay quality metric based on signal window and variability; values closer to 1 indicate a more robust assay (often, ≥0.5 is considered excellent).

- IC50: Concentration of an inhibitor that reduces activity by 50%.

- EC50: Concentration of an activator/agonist that produces 50% of the maximal effect.

- SAR (Structure–Activity Relationship): Relationship between chemical structure changes and changes in biological activity.

- LIMS: Laboratory Information Management System for tracking samples, plates, results, and provenance.

- ELN: Electronic Laboratory Notebook for experimental records and workflows.

- FRET / TR-FRET: Proximity-based fluorescence readouts; TR-FRET uses time-resolved detection to reduce background.

- BRET: Proximity readout driven by bioluminescence rather than excitation light.

- PAINS: Pan-assay interference compounds that frequently cause false positives due to assay interference mechanisms.

- Orthogonal assay: A follow-up assay using a different readout to confirm true activity.

- Counterscreen: Assay designed to detect artifacts or off-target activity (e.g., reporter interference).

- ADMET: Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity.

References

- Baell, J. B., Nissink, J. W. M., 2018, Seven Year Itch: Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) in 2017 – Utility and Limitations, ACS Chem. Biol., 13, 36-44. doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.7b00903

- Banait, A. S., et al., 2025, Advancing Drug Discovery and Material Science Using Quantum Simulations for Molecular Structures, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Management & Machine Intelligence, 43, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3745812.3745862

- Blay. V. et al., 2020, High-Throughput Screening: today’s biochemical and cell-based approaches, Drug Discov. Today, 25, 10, 1807-1827. doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2020.07.024

- Boldini, D. et al., 2024, Machine Learning Assisted Hit Prioritization for High Throughput Screening in Drug Discovery, ACS Cent. Sci., 10, 4, 823-832. doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.3c01517

- Chen, L. et al., 2016, mQC: A Heuristic Quality-Control Metric for High-Throughput Drug Combination Screening, Sci. Rep., 6, 37741. doi.org/10.1038/srep37741

- Chieng, A., Wan, Z., Wang, S., 2024, Recent Advances in Real-Time Label-Free Detection of Small Molecules, Biosensors, 2024, 14 (2), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios14020080

- Dahlin, J. L., Walters, M. A., 2014, The essential roles of chemistry in high-throughput screening triage, Future Med. Chem., 6, 11, 1265-1290. doi.org/ 10.4155/fmc.14.60

- Danishuddin, et al., 2025, Quantum intelligence in drug discovery: Advancing insights with quantum machine learning, Drug Discov Today, 30 (10), 104432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2025.104463

- Das, D. et al., 2025, Recent Advances in Antibody Discovery Using Ultrahigh-Throughput Droplet Microfluidics: Challenges and Future Perspectives, Biosensors, 15 (7), 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15070409

- LabKey: What is High-Througput Screening? (2024). What is High-Throughput Screening (HTS)? | LabKey

- Leung, C. M. et al., 2022, A guide to the organ-on-a-chip, Nat Rew Methods Primers, 2, 33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00118-6

- Ma, C. et al., 2021, Organ-on-a-Chip: A New Paradigm for Drug Development, Trends Pharmacol. Sci., 42, 2, 119-133. doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2020.11.009

- Macarron, R. et al., 2011, Impact of high-throughput screening in biomedical research, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov., 10, 3, 188-195. doi.org/10.1038/nrd3368

- Mayr, L. M., Fuerst, P., 2008, The Future of High-Throughput Screening, J. Biomol. Screen., 443-448.

- Meissner, F. et al., 2022, The emerging role of mass spectrometry-based proteomics in drug discovery, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov., 21, 637-654. doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00409-3

- Seat, S., et al., 2024, A Decade in a Systematic Review: The Evolution and Impact of Cell Painting, bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.04.592531

- Smith, R. et al., 2025, Twenty-Five years of High-throughput Screening of Biological Samples with Mass Spectrometry: Current Platforms and Emerging Methods, ChemRxiv. https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-db46t

- Song, S-H., Jeong, S., 2024, State-of-the-art in high throughput organ-on-chip for biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, Clin Exp Reprod Med, 52 (2), 114-124. https://doi.org/10.5653/cerm.2024.06954

- Subramani, C. et al., 2024, High content screening strategies for large-scale compound libraries with a focus on high-containment viruses, Antiviral Research, 221, 105764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2023.105764

- TheScientist: The Latest in Lab Automation (2023). The Latest in Lab Automation | The Scientist

- TheScientist: An Overview of High Throughput Screening (2024). An Overview of High Throughput Screening | The Scientist

- Van Goor, F. et al., 2009, Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106 (44), 18825-18830. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0904709106

- Vertex: FDA Approves KALYDECO™ (ivacaftor), the First Medicine to Treat the Underlying Cause of Cystic Fibrosis (2012). https://investors.vrtx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-approves-kalydecotm-ivacaftor-first-medicine-treat

- Wang, Y., Jeon, H. 2022, 3D cell cultures toward quantitative high-throughput drug screening, Trends Pharmacol. Sci., 43, 7, 569-581

- Winter, M. et al., 2023, Label-free high-throughput screening via acoustic ejection mass spectrometry put into practice, Slas Discov, 28 (5), 240-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.slasd.2023.04.001

- Yang, Q. et al., 2025, Advanced droplet microfluidic platform for high-throughput screening of industrial fungi, Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 285, 117594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2025.117594

- Zhang, J-H., Chung, T. D., Oldenburg, K. R., 1999, A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays, J Biomol Screen, 4 (2), 67-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705719900400206

Related Services

| Service | |

|---|---|

Small molecule drug discovery for even hard-to-drug targets – identify inhibitors, binders and modulators | |

Molecular Glue Direct | |

PPI Inhibitor Direct | |

Integral membrane proteins | |

Specificity Direct – multiplexed screening of target and anti-targets | |

Express – optimized for fast turn – around-time | |

Snap – easy, fast, and affordable |