Receptors as Drug Targets: Intracellular Ligand Discovery Using DNA-Encoded Libraries

Receptors sit at the heart of biology’s information flow. They detect extracellular cues (hormones, neurotransmitters, chemokines, growth factors), translate them into intracellular signals, and control everything from metabolism and immune responses to neural function and cell fate. Because receptor activity can be tuned, or redirected with the right ligand, receptors have become some of the most valuable and most intensively pursued drug targets.

Among receptor families, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are especially prominent: a recent review analyzing the “drugged GPCRome” reports 516 approved drugs targeting GPCRs (~36% of all approved drugs). [17] That scale is exactly why receptor programs are so competitive and why teams increasingly seek technologies that can uncover new chemotypes, new binding sites (including allosteric pockets), and better starting points for medicinal chemistry.

One of the most effective modern approaches for doing this is DNA-encoded library (DEL) screening. DELs link each small molecule to a DNA barcode, enabling massively parallel affinity-driven selections and rapid identification of binders by sequencing. The core concept traces back to early “encoded combinatorial chemistry” work, which since 1990 has matured into an industry workhorse for hit discovery. [1][2]

For receptor programs, DEL screening offers something particularly attractive:

- Receptors are ligand-driven targets, often with multiple conformations and multiple druggable pockets.

- DEL screening can sample very large chemical space efficiently compared with classical plate-based high-throughput screening (HTS). [2]

- DELs can be adapted to challenging receptor formats, including purified membrane receptors in detergent or nanodiscs, and increasingly to live-cell or in-cell selection strategies. [6][7][8][22]

That said, a successful receptor program is rarely “one-tech-only.” Receptor discovery is a pipeline problem: you want the right starting points and the right evidence early – binding, target engagement, selectivity, and functional impact. So, in this article, we’ll take a broader view: how receptors behave as drug targets, how ligands are discovered across multiple discovery paradigms, and where DEL fits best; especially for organizations seeking receptor ligand discovery services, small molecule receptor binders, and a practical receptor drug discovery platform that can handle hard receptor formats.

Receptors as ligand-driven drug targets

Receptors in cellular signaling

Receptors can be viewed as “signal processors.” Ligands don’t just turn receptors on or off; they can stabilize specific receptor states, bias signaling toward particular pathways, and change receptor localization or trafficking. This is particularly visible in GPCR pharmacology, where allosteric modulation and state-dependent signaling have become central to modern drug discovery thinking. [9][10]

A helpful way to frame receptor pharmacology (especially for GPCRs) is that ligands can act as:

- Orthosteric ligands that compete with endogenous agonists at the primary binding site.

- Allosteric modulators that bind elsewhere to tune potency/efficacy, improve selectivity, or alter signaling bias.

- Bitopic ligands that engage both orthosteric and allosteric regions (in some receptor systems), often blending affinity with selectivity and unique pharmacology (conceptually aligned with allosteric principles discussed in GPCR allostery reviews). [9][10]

These concepts matter because they directly influence what you screen for and how you interpret hits. A selection or screen that only reports “binding” may miss functional nuance, while a functional assay may miss silent binders that become valuable after optimization or when paired with a second ligand (e.g., Positive Allosteric Modulator [PAM] discovery).

Therapeutic importance of receptor modulation

The medical reach of receptors is enormous:

- GPCRs: CNS, cardiometabolic disease, inflammation, respiratory disease, pain relief, pain treatment, and more (with a very large fraction of approved medicines). [17]

- Enzyme-linked receptors (e.g., receptor tyrosine kinases): oncology, immune disease, fibrosis – often targeted with biologics and small molecules.

- Nuclear receptors: endocrine and metabolic disorders, inflammation, oncology; often with small molecules that tune transcriptional programs. [14][15][16]

In other words, receptors remain high-value targets and high-competition targets. That combination increases the premium on discovery strategies that can yield novel chemotypes, allosteric ligands, and selective binders that can be translated into function.

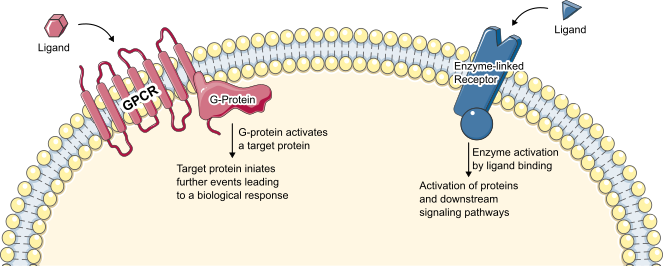

Figure 1: Overview of cell-membrane receptors G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and Enzyme-linked receptors.

Why receptor ligand discovery is difficult (and why many “good hits” fail)

Receptor ligand discovery isn’t hard because receptors are “undruggable.” It’s hard because receptors are contextual – their ligandability and pharmacology can shift with receptor state, membrane environment, binding partners, and assay format.

Conformational ensembles, state dependence, and multiple pockets

Many receptors exist as ensembles of states whose populations depend on ligand, membrane composition, binding partners, and modifications. For GPCRs, this is the basis for concepts like partial agonism, biased agonism, and ligand-specific receptor conformations – phenomena that are deeply intertwined with allosteric modulation. [9][10]

In practice, this means:

- An assay that traps one receptor state can enrich ligands for that state.

- Ligands can be “real” binders but non-productive for the pathway you care about.

- Allosteric sites can deliver selectivity advantages but hit rates can be low and effects can be subtle. [9][10]

Membrane proteins are format-sensitive

GPCRs and other integral membrane receptors often need stabilizing conditions (detergents, lipids, nanodiscs, stabilizing mutations, binding partners). These conditions can alter which sites are accessible and which conformations dominate. Nanodiscs, for example, are widely used to present membrane proteins in a controlled lipid environment and are broadly recognized as powerful tools in membrane protein biochemistry and biophysics. [8]

From a discovery standpoint, “format sensitivity” shows up as:

- Variable protein stability (aggregation, denaturation, loss of native pharmacology).

- Shifts in orthosteric/allosteric site accessibility.

- Higher background binding from hydrophobic compounds in membrane-like environments.

Binding vs function is not the same gate

A binder can be:

- a true receptor ligand with a useful functional profile,

- a binder that fails to engage in cells,

- a binder that hits a non-productive state,

- or a binder that is “real” but not developable (solubility, permeability, off-targets).

A robust receptor strategy accepts this reality: you need both efficient hit-finding and efficient triage. That’s why modern receptor discovery programs increasingly combine hit-finding technologies (HTS, fragments, DEL, computational methods) with early orthogonal validation and functional profiling.

The receptor ligand discovery toolbox: beyond any single screening method

When teams search for receptor ligand discovery services or a receptor drug discovery platform, they’re usually weighing a portfolio of discovery routes, not just one. Different approaches shine at different points in the funnel: some are great at generating starting points, others excel at characterizing mechanisms or accelerating optimization.

1) Classical high-throughput screening (HTS)

HTS tests large numbers of compounds (often hundreds of thousands) using biochemical or cell-based assays. It remains a major pillar of drug discovery because it can be directly functional if the assay is designed that way. [13]

Where HTS excels

- When you have a robust functional assay (e.g., GPCR signaling readout).

- When you want early functional triage.

- When the target behaves well in assay conditions.

Where HTS struggles for receptors

- Assay development for receptors can be slow and artifact-prone (signal window, receptor expression variability, pathway coupling).

- Membrane receptor formats can create background noise or stability issues.

- Chemical space is limited by practical library size and cost compared with pooled approaches. [13]

HTS remains a strong option when the biology is well understood and the assay behaves, but for receptors that are unstable, require specific complexes, or signal in context-dependent ways, HTS can become resource-intensive early in a program.

2) Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) (H3)

Fragment screening uses small, low-complexity molecules (“fragments”) to efficiently sample chemical space and then grows or links them into potent ligands. FBDD is now mainstream, with a long pipeline of fragment-derived clinical candidates noted in an influential review. [11]

For GPCRs, fragment screening has historically been constrained by receptor stability in detergents and the sensitivity needed to detect weak fragment binding. Stabilized GPCR constructs (often referred to in the context of “StaR” GPCRs) and biophysical workflows have been used to enable fragment screening against GPCRs. [12]

Where FBDD excels

- When you have strong structural biology and biophysics.

- When you want highly ligand-efficient starting points.

- When you can stabilize the receptor and obtain reliable binding measurements. [11][12]

Where FBDD struggles

- Weak affinities demand sensitive, well-behaved receptor preparations.

- Progress can bottleneck on structural cycles and chemistry.

- Some receptor targets remain difficult to stabilize or measure with adequate throughput.

3) Structure-based and computational approaches

Structure-guided discovery is increasingly relevant for receptors, especially as structural coverage has expanded across GPCR families and nuclear receptors. In practice, structure-based tools are often most powerful after you have at least one validated chemotype – because they become tools for optimization, selectivity engineering, and hypothesis testing rather than purely for hit generation.

Even when computational approaches are used earlier (virtual screening, pharmacophore models), they typically benefit from experimental anchors, known ligands, binding-site constraints, or assay data that reduces the search space.

4) Biologics, peptides, and alternative modalities

Many receptors, especially extracellular or cell-surface receptors are effectively targeted by antibodies, peptides, or engineered proteins. Small molecules still matter profoundly (especially for intracellular receptor domains, GPCRs, and nuclear receptors), but a modern receptor portfolio often includes multiple modalities depending on mechanism, tissue access, and safety constraints. The practical takeaway is that “receptor targeting” is modality-agnostic; what changes is the discovery and validation toolkit.

5) DNA-encoded library (DEL / DECL) screening

DEL is a different engine: instead of testing compounds one-by-one, you screen pools of DNA-tagged compounds and identify enriched binders by sequencing. Modern DEL approaches and selection formats are covered in widely cited reviews. [2][3][4]

DEL screening is particularly relevant to receptor teams searching for:

- DNA encoded library receptor screening

- DNA encoded library screening for receptors

- DEL screening for GPCR targets

- small molecule receptor binders

- hit identification for receptor targets

- receptor ligand discovery outsourcing

But DEL screening should be understood in a broader workflow: DEL screening can be a powerful front-end binder discovery tool – especially when paired with strong validation and functional follow-up.

Receptor classes and target formats: what you can screen (and how)

A frequent misconception is that receptor programs can be categorized simply by receptor class (GPCR vs nuclear receptor vs RTK). The more predictive way to plan discovery is by format: purified domain vs full-length receptor, membrane mimetic vs cellular presentation, and the degree to which functional partners must be retained.

GPCR ligand screening

GPCR programs often seek orthosteric ligands, allosteric modulators (PAM/NAM), or ligands that bias pathway output. Reviews of GPCR allostery emphasize how allosteric ligands can fine-tune receptor function and often offer selectivity advantages compared with orthosteric ligands. [9][10]

DEL precedent for GPCRs

A notable peer-reviewed study demonstrated an allosteric “beta-blocker” for the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) discovered via a DNA-encoded library selection against a purified GPCR. [5] This is a useful proof point: DEL can access GPCR allosteric chemistry when the receptor is presented in a workable format and selection conditions support that binding mode.

Why GPCR format choices matter

GPCRs are among the most format-sensitive targets in drug discovery. Depending on the receptor and hypothesis, teams may choose:

- Purified receptor preparations (often stabilized, with defined partners)

- Detergent-solubilized receptor

- Receptor embedded in nanodiscs (a more native-like lipid environment) [8]

- Live-cell or in-cell strategies when native context is essential for maintaining function or state distributions [6][7]

Even within a “GPCR ligand screening” project, multiple formats are often used sequentially: a binder discovery format (purified receptor or cell-based selection), followed by orthogonal binding assays and cellular function assays.

Nuclear receptor ligand identification

Nuclear receptors are intracellular transcription factors that regulate gene expression through ligand-dependent recruitment of coactivators and corepressors. Foundational and modern reviews describe the breadth of the nuclear receptor superfamily and the structural basis of ligand-driven receptor regulation. [14][15][16]

For nuclear receptor ligand identification, screening is often feasible with soluble ligand-binding domains or curated receptor complexes. The most common downstream validation steps include:

- Orthogonal binding assays (biophysical or competition binding)

- Coactivator recruitment assays (often energy transfer formats)

- Transactivation reporter assays and gene expression studies

Because nuclear receptors are frequently “ligandable” but biologically nuanced (partial agonism, tissue-selective signaling), the ability to profile functional outcomes early can be as important as potency.

Enzyme-linked receptors and other receptor families

Receptor tyrosine kinases, cytokine receptors, and other signaling receptors may be addressed by small molecules (intracellular domains, allosteric sites, PPIs) or biologics. For small-molecule discovery, the same general principles apply; choose the right target format, use a discovery method compatible with that format, and validate with orthogonal evidence.

For example, even when the extracellular receptor is targeted by biologics, the intracellular kinase domain may be targeted by small molecules making “receptor drug discovery” a spectrum of projects rather than a single category.

Receptor binding assays and validation: the “truth stage” after screening

Regardless of how you find initial hits (HTS, fragments, DEL, or computational) you need to establish confidence. For receptors, that usually means orthogonal confirmation plus functional profiling. This is also where many programs gain speed: the better your validation plan, the faster you can discard false positives and focus chemistry on the most promising series.

Orthogonal binding confirmation (examples)

Common receptor binding assays include:

- Biophysical binding (e.g., SPR/BLI) when receptor preparations are compatible and stable

- Competition binding (radioligand or fluorescent ligand), frequently used for GPCR orthosteric sites

- Proximity/energy transfer binding assays (e.g., TR-FRET/HTRF) when labeled reagents are available and the format is well behaved

For GPCRs and fragile membrane proteins, the choice of assay often hinges on receptor stability and presentation format; again highlighting why nanodiscs and stabilized receptors are important enabling technologies. [8][12]

Functional follow-up (examples)

Binding becomes therapeutically meaningful only once you understand functional outcomes. Typical functional assays include:

For GPCRs

- Second messenger assays (cAMP, IP1)

- Calcium flux

- β-arrestin recruitment

- Pathway panels to capture bias (when appropriate)

For nuclear receptors

- Coactivator recruitment assays

- Transactivation reporter assays

- Transcriptomics or targeted gene expression panels

Key point: You can’t run a receptor program effectively unless your hit discovery approach is tightly coupled with a realistic validation plan. This is especially relevant for outsourcing: strong receptor ligand discovery services don’t stop at “hit lists” – they emphasize off-DNA synthesis (when relevant), orthogonal confirmation, and a credible path to functional understanding.

Target presentation: the practical decision that determines success

Receptors often fail at screening not because “the library” is wrong, but because the receptor wasn’t presented in a biologically and biophysically meaningful way.

Purified receptors: immobilization vs in-solution strategies

Purified receptors can be used in multiple assay architectures. For pooled selection technologies (including DEL), there are multiple ways to execute selection and capture, and the field has continued to innovate on selection formats and controls. [2][4]

In general:

- Immobilization/capture can provide clean separation but risks perturbing conformation if the receptor is constrained or oriented poorly.

- In-solution approaches can preserve native-like behavior but demand careful handling to control background binding and maintain receptor stability.

For receptors, the best approach is often the one that minimizes artifacts for that specific target while enabling robust counter-selection design.

Detergent vs nanodisc formats for membrane receptors

Nanodiscs are widely used membrane mimetics and are considered powerful for membrane protein studies because they provide control over lipid environment and size while preserving many aspects of native membrane protein behavior. [8]

For receptor ligand discovery, this matters because lipid context can influence:

- pocket accessibility,

- receptor stability,

- active/inactive state distributions,

- and background binding.

Some receptors behave acceptably in detergent, while others show better stability and pharmacology in nanodiscs. Even for the same receptor, different project goals (orthosteric competition vs allosteric site discovery vs state-selective ligand discovery) can shift the optimal format.

Live-cell and in-cell approaches (native context)

Two peer-reviewed examples illustrate how screening can move toward native receptor context:

- DEL selection against endogenous membrane proteins on live cells: a strategy enabling target-specific DEL selections on live cells for endogenous membrane targets. [6]

- DEL screening inside a living cell: a demonstration described as the first successful screening of a multimillion-member DEL inside a living cell. [7]

Not every receptor project needs live-cell or in-cell selection, but when target purification disrupts the biology or when native context is essential, these approaches can be strategically valuable. For example, projects involving native receptor complexes, fragile receptors, or receptors whose relevant conformations are stabilized by cellular components may benefit from formats closer to biology.

Where DEL fits in a broader receptor discovery strategy

DEL is best seen as one high-leverage engine in a receptor discovery toolbox – not a replacement for everything else.

What DEL is especially good at for receptors

- Exploring huge chemical space efficiently relative to plate-based screening. [2]

- Producing multiple series (clusters) that provide options for selectivity and developability.

- Identifying small molecule receptor binders even when hit rates are low (common for allosteric sites).

- Supporting difficult target formats when appropriate selection architectures exist, including advanced selection methodologies and cell-context approaches described in the literature. [3][4][6][7]

Where DEL should be paired with other approaches

- If your key risk is functional mechanism, you may want early functional assays to triage binders quickly.

- If your key advantage is structure-guided optimization, fragment screening or structure-driven workflows may complement DEL series finding. [11][12]

- If your receptor is highly context-dependent, live-cell/in-cell selection or cell-based functional assays may be essential. [6][7]

This is exactly why “fragment vs DEL receptor screening” is often the wrong framing. The real question is: What is the fastest route to validated, optimizable chemotypes for your receptor, given your constraints? Many teams deliberately run two complementary engines in parallel, one that maximizes breadth (DEL or HTS), and one that maximizes interpretability (fragments/structure/biophysics), then converge on the strongest series.

DEL vs HTS vs fragment screening for receptors (a pragmatic comparison)

DEL vs HTS for GPCR targets

- HTS: functional-first but can be limited by library size and assay complexity; still very powerful if you have a clean GPCR functional assay and robust automation. [13]

- DEL: binding-first with enormous library scale; strong for finding novel binders (including allosteric) but requires deliberate validation and functional triage. [2][3][4]

A practical way to decide is to ask: Is my gating risk “finding any chemotype that binds” or “finding the right functional phenotype”? If binding discovery is the bottleneck (often true for selectivity-driven or allosteric programs), DEL can be a high-return front end. If functional phenotype is the bottleneck (e.g., bias, partial agonism, pathway selectivity), you may prioritize early functional screening or rapidly move DEL hits into functional assays.

Fragment vs DEL receptor screening

- Fragments: superb ligand efficiency; excellent when you have stabilized receptors and a robust structural/biophysical engine; proven for GPCRs with stabilized constructs. [11][12]

- DEL: scale-driven series discovery; can deliver multiple chemotypes fast; especially attractive for hard-to-hit pockets where you need breadth and novelty. [2][4]

Many receptor programs combine both: fragments provide high-quality anchors for rational optimization, while DEL provides breadth and alternative scaffolds that may solve selectivity, permeability, or IP landscape challenges.

A useful decision heuristic

- Start with DEL when your main risk is “we need novel chemotypes and multiple starting points quickly,” especially for competitive receptor landscapes.

- Start with FBDD when your main advantage is “we can stabilize the receptor and run structure-guided cycles efficiently.”

- Use HTS when the assay is robust and your program requires functional triage at scale early. [13]

Case study: State-steered screening for allosteric receptor modulators

A 2024 Nature study illustrates how receptor conformational biology can be exploited to discover differentiated ligands: O’Brien and colleagues screened an ultra-large (~4.4 billion member) DNA-encoded chemical library against the inactive, naloxone-bound μ-opioid receptor (μOR) while counter-screening against the active, Gi/agonist-bound receptor to “steer” enrichment toward conformation-selective negative allosteric modulators (NAMs). This strategy yielded a single, strongly enriched NAM (compound 368) that enhanced naloxone binding affinity (reported EC50 ~133 nM in radioligand binding) and worked cooperatively with naloxone to potently suppress μOR signaling. Cryo-EM revealed that 368 binds the extracellular vestibule, directly contacting naloxone while stabilizing a distinct inactive extracellular conformation (notably involving TM2/TM7), reshaping orthosteric ligand kinetics in therapeutically favorable ways. In vivo, the NAM combined with low-dose naloxone more effectively reversed morphine- and fentanyl-driven behaviors while reducing withdrawal-like effects compared with conventional high-dose naloxone – highlighting how state-steered DEL screening can uncover receptor modulators with clinically relevant pharmacology. [22]

A practical workflow for receptor ligand discovery (service-ready view)

Whether you run this internally or via receptor ligand discovery outsourcing, the workflow below is a useful “minimum viable” path from receptor target to validated hits.

Step 1: Define the target hypothesis and desired ligand profile

Clarify:

- Orthosteric vs allosteric intent

- Desired mechanism (agonist, antagonist, inverse agonist, PAM/NAM)

- Selectivity needs (subtype, off-target risk)

- Biological context that must be preserved (membrane lipids, partners, modifications)

This step seems obvious, but it is the most common source of “screening mismatch.” If your therapeutic hypothesis requires an active-state binder or a pathway-biased ligand, you should reflect that early in assay design and target presentation choices (even if your first-stage method is “binding-first”). [9][10]

Step 2: Choose the screening route(s)

Options include:

- Functional screening (HTS-like)

- Binding-first approaches (DEL, fragments)

- Combined strategies (e.g., DEL for breadth + functional assays for triage)

DEL and fragment methods have strong review coverage; selection format choice often matters as much as the underlying library. [2][3][4][11]

Step 3: Choose target presentation

For membrane receptors, decide:

- detergent vs nanodiscs, stabilized vs wild-type,

- purified vs cell-based vs in-cell.

Nanodisc-based approaches are widely recognized as powerful for membrane proteins and are often chosen specifically to better preserve functional states. [8]

Step 4: Run screening + counter-screens

For receptors, counter-screens are not optional if you want clean series:

- matrix/capture controls,

- related receptor subtype controls,

- “sticky” membrane controls for integral membrane formats.

DEL reviews emphasize the importance of selection design and controls for reducing artifacts and improving hit quality. [2][4]

Step 5: Hit identification and validation

This is where screening becomes drug discovery:

- follow-up chemistry (including off-DNA resynthesis for DEL-derived hits),

- orthogonal receptor binding assays,

- selectivity panels as needed,

- early functional readouts to sort mechanism.

For GPCR targets, allosteric effects can be context-dependent, which is why parallel functional assays (or pathway panels) can be particularly informative once you have confirmed binding. [9][10]

Step 6: Build SAR and move toward leads

Once you have at least one validated series:

- iterate medicinal chemistry with functional and selectivity feedback,

- apply structural methods where available,

- prioritize developability (solubility, permeability, stability) early.

In practice, this is where multiple hit series payoff: you can choose the series that best balances potency, selectivity, and developability rather than trying to “force” a single series through optimization.

Vipergen’s role: receptor ligand discovery services with DEL specialization (without the blinders)

Vipergen focuses on DNA encoded library screening for receptors as part of a broader hit discovery and validation workflow, with specific emphasis on difficult targets and advanced selection formats.

From a receptor perspective, two capabilities are especially relevant:

- In-solution selection architecture (BTE)

Vipergen’s Binder Trap Enrichment (BTE) is an emulsion-based method to isolate binding pairs and preserve binding information via ligation. This can be useful when immobilization creates artifacts or when you want selection in solution. [20] Membrane receptor screening formats (detergent or nanodiscs)

Vipergen describes DEL screening services for purified biotinylated integral membrane proteins formulated in nanodiscs or detergent, a practical option for GPCRs and other membrane receptors where target folding and stability are limiting factors. [18][8] - In-cell selection (cBTE) for physiologically relevant target engagement

Vipergen describes Cellular Binder Trap Enrichment (cBTE) as an approach for DEL screening inside living cells, aligning with the broader scientific direction demonstrated in peer-reviewed literature on intracellular DEL screening. [19][7]

Importantly, the “broader” takeaway is this: Vipergen’s DEL tools are most valuable when used as part of a receptor pipeline that also includes orthogonal receptor binding assays and functional follow-up because receptor success requires binding, engagement, selectivity, and mechanism to line up. [21]

FAQ

DNA encoded library receptor screening (also called DNA-encoded chemical library or DECL screening) is a binder discovery approach where DNA-barcoded small molecules are selected against a receptor target, enriched binders are decoded by sequencing, and representative hits are resynthesized and validated. The conceptual origin and modern implementation are described in landmark peer-reviewed sources. [1][2][3]

Yes. Peer-reviewed work has shown DEL selection against purified GPCRs can yield meaningful ligands, including GPCR allosteric ligands in the β2AR system. [5]

Nuclear receptors are a major drug discovery class with a deep structural and mechanistic literature. Their ligand-binding domains can often be handled as soluble proteins for screening and follow-up. [14][15][16]

If you have stabilized receptor preparations and a strong biophysical/structural workflow, fragment screening can be excellent – even for GPCRs using stabilized constructs. If you need rapid, broad exploration of chemical space and multiple series, DEL can be a strong route. [11][12][2]

Peer-reviewed studies demonstrate DEL selection on live cells against endogenous membrane proteins and DEL screening inside living cells. [6][7]

Conclusion: build receptor programs around evidence, not ideology

Receptor drug discovery rewards teams that combine biological realism with experimental efficiency. HTS can be functional-first but assay-heavy; fragments can be structure-friendly but format-sensitive; DEL can be scale-dominant but validation-dependent. The strongest receptor programs treat these as complementary tools and design workflows that quickly move from binder discovery to validated target engagement to functional mechanism. [13][11][12]

Within that broader toolkit, DNA-encoded library screening for receptors is a powerful accelerator especially when receptor format is challenging (membrane proteins) or when novelty is essential (allosteric pockets, subtype selectivity). With appropriate target presentation (including nanodiscs where helpful), rigorous orthogonal validation, and early functional profiling, DEL-derived chemotypes can become high-quality starting points for medicinal chemistry and lead discovery. [2][8][9][10]

References

-

- Brenner S, Lerner RA. Encoded combinatorial chemistry. PNAS, 89(12), 5381-5383 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.89.12.5381

- Goodnow RA Jr, Dumelin CE, Keefe AD. DNA-encoded chemistry: enabling the deeper sampling of chemical space. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 16, 131-147 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2016.213

- Gironda-Martínez A, Donckele EJ, Samain F, Neri D. DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries: A Comprehensive Review with Success Stories and Future Challenges. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, 4, 4, 1265-1279 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsptsci.1c00118

- Satz AL, Kuai L, Peng, X. Selections and screenings of DNA-encoded chemical libraries: current state and future perspectives. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 39, 127851 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.127851

- Ahn S, et al. Allosteric “beta-blocker” isolated from a DNA-encoded small molecule library. PNAS, 114 (7), 1708-1713 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620645114

- Huang Y, et al. Selection of DNA-encoded chemical libraries against endogenous membrane proteins on live cells. Nature Chemistry, 13, 77-88 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-020-00605-x

- Petersen LK, et al. Screening of DNA-Encoded Small Molecule Libraries inside a Living Cell. JACS, 143, 7, 2751-2756 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c09213

- Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Nanodiscs in Membrane Biochemistry and Biophysics. Chemical Reviews, 117 (6), 4669-4713 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00690

- May LT, Leach K, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Allosteric modulation of G protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 47, 1-51 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105159

- Keov P, et al. Allosteric modulation of G protein-coupled receptors: a pharmacological perspective. Neuropharmacology, 60, 1, 24-35 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.010

- Erlanson DA, et al. Twenty years on: the impact of fragments on drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 15, 605-619 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2016.109

- Congreve M, et al. Fragment Screening of Stabilized G-Protein-Coupled Receptors Using Biophysical Methods. Methods in Enzymology, 493, 115-136 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-381274-2.00005-4

- Carnero A. High throughput screening in drug discovery. Clinical and Translational Oncology, 8 (7), 482-490 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-006-0048-2

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell, 83, 835-839 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x

- Huang P, Chandra V, Rastinejad F. Structural Overview of the Nuclear Receptor Superfamily. Annual Review of Physiology, 72, 247-272 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135917

- Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear Receptors, RXR, and the Big Bang. Cell, 157 (1), 255-266 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.012

- Lorente JS, et al. GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nature Review Drug Discovery, 24 (6), 458-479 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-025-01139-y

- Vipergen – DEL screening for integral membrane proteins. https://www.vipergen.com/del-integral-membrane-proteins/

- Vipergen – Cellular Binder Trap Enrichment (cBTE). https://www.vipergen.com/cellular-binder-trap-enrichment/

- Vipergen – Binder Trap Enrichment (BTE). https://www.vipergen.com/binder-trap-enrichment-bte/

- Vipergen – Drug discovery services overview. https://www.vipergen.com/revolutionizing-research-with-chemical-libraries/

- O’Brien, et al. A µ-opioid receptor modulator that works cooperatively with naloxone. Nature, 631, 686-693 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07587-7

Related Services

| Service | |

|---|---|

Small molecule drug discovery for even hard-to-drug targets – identify inhibitors, binders and modulators | |

Molecular Glue Direct | |

PPI Inhibitor Direct | |

Integral membrane proteins | |

Specificity Direct – multiplexed screening of target and anti-targets | |

Express – optimized for fast turn – around-time | |

Snap – easy, fast, and affordable |