Small Molecule Drug Discovery: Principles, Processes, and Molecular Design for Optimal Therapeutic Efficacy

Introduction

At the same time, small molecule drug discovery is an inherently high-risk, high-attrition endeavor. Of the thousands of compounds synthesized and screened, only a handful advance to clinical development, and fewer still achieve regulatory approval. This reality has driven the field to adopt increasingly sophisticated strategies—integrating medicinal chemistry, computational drug design, high-throughput screening, ADMET prediction, and artificial intelligence—to improve efficiency and decision-making earlier in the pipeline.

This review provides a comprehensive, end-to-end perspective on small molecule drug discovery, structured as a logical progression from foundational principles to advanced methodologies and future directions. Rather than treating drug-likeness as a standalone filter, we emphasize how physicochemical properties, ADMET behavior, and molecular design principles are continuously applied throughout the discovery workflow, shaping success or failure at every stage.

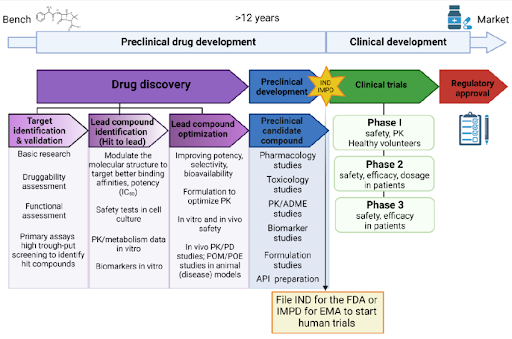

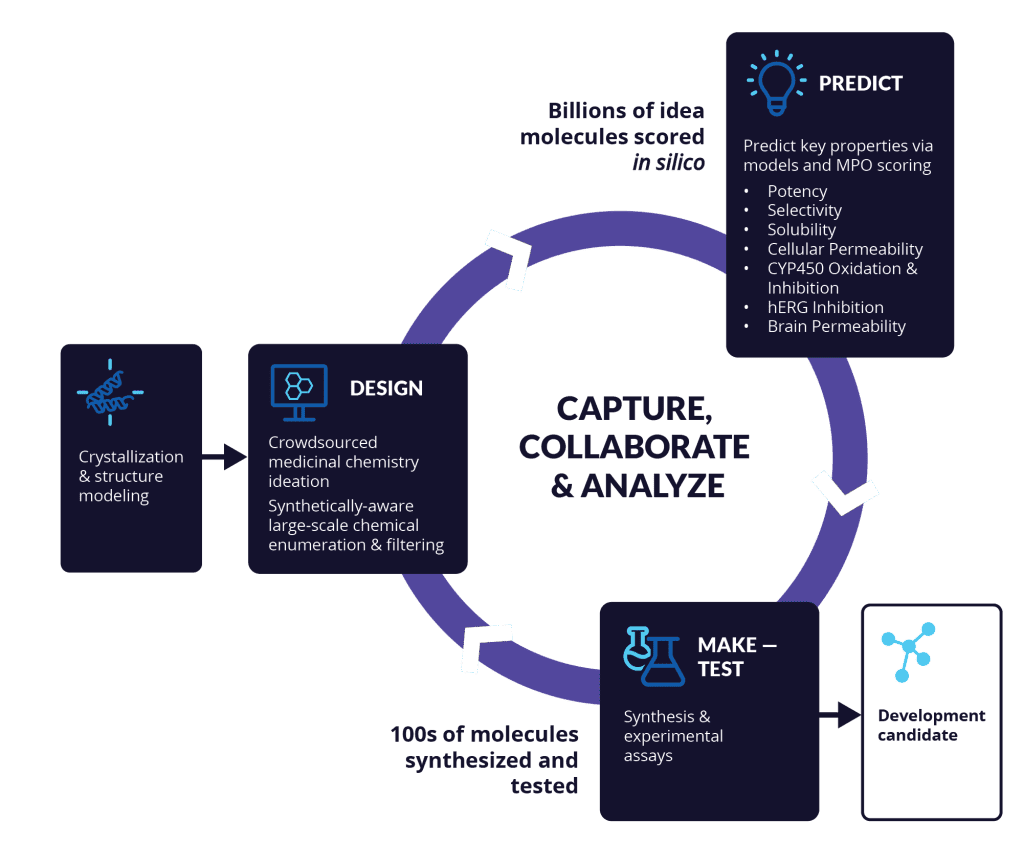

Figure 1 | Conceptual overview of small molecule drug discovery.

Small molecule drug discovery integrates disease biology, medicinal chemistry, and pharmacology to translate biological hypotheses into clinically viable therapeutics. The process spans target identification and validation, compound screening, iterative chemical optimization, and preclinical development, with drug-likeness and ADMET considerations guiding decision-making at every stage. Advances in computational chemistry, structural biology, and artificial intelligence increasingly augment traditional experimental approaches, improving efficiency and reducing attrition.

Understanding Small Molecule Drugs: Definition, Characteristics, and Historical Impact

Key Characteristics of Small Molecule Therapeutics

Several features distinguish small molecules from larger biologic modalities:

- Chemical diversity: Small molecules occupy a vast chemical space, enabling fine-tuned optimization of potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetics.

- Cell permeability: Their size and physicochemical properties often allow access to intracellular targets inaccessible to antibodies.

- Manufacturing scalability: Synthetic chemistry enables robust, cost-effective, and reproducible production.

- Formulation flexibility: Oral, transdermal, inhaled, and injectable formulations are feasible.

Historically, small molecules have driven transformative advances in medicine, from antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs to kinase inhibitors and antiviral agents. Even as biologics expand therapeutic options, small molecules remain indispensable—particularly in chronic diseases, global health, and precision oncology.

The Small Molecule Drug Discovery Pipeline: A Multi-Stage Journey

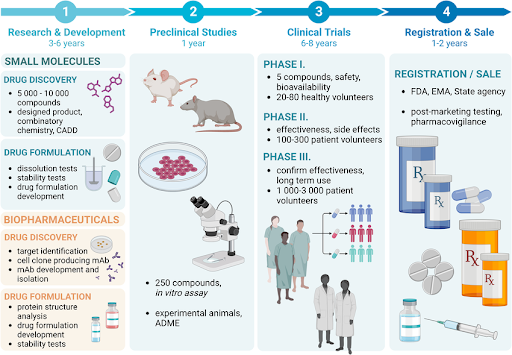

Figure 2 | The multi-stage small molecule drug discovery pipeline.

The discovery process proceeds through target identification and validation, hit identification, hit-to-lead optimization, lead optimization, and preclinical development. Although depicted sequentially, the pipeline is highly iterative, with feedback loops between chemistry, biology, and ADMET profiling. Early-stage decisions—particularly target choice and physicochemical property control—strongly influence downstream success and clinical translatability.

Small molecule drug discovery is best understood as a multi-stage, iterative process, not a linear handoff. Decisions made at early stages—especially around target selection and chemical properties—reverberate throughout development.

At a high level, the pipeline comprises:

- Target identification and validation

- Hit identification

- Hit-to-lead optimization

- Lead optimization

- Preclinical development

Each stage integrates considerations of drug-likeness, ADMET, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics (PD), progressively increasing confidence that a candidate can become a safe and effective medicine.

Target Identification and Validation

Target identification begins with a deep understanding of disease biology. The goal is to identify a molecular entity whose modulation produces a therapeutically meaningful effect with an acceptable safety margin.

Disease Biology and Target Selection

Modern target discovery increasingly relies on systems-level data, including:

- Genomics and human genetics (e.g., disease-associated variants)

- Transcriptomics and proteomics

- Pathway and network analysis

- Clinical phenotype correlations

Targets supported by strong human genetic evidence tend to show higher clinical success rates, underscoring the value of early biological validation.

Target Validation Strategies

Validation seeks to establish a causal relationship between target modulation and disease outcome. Common approaches include:

- Genetic perturbation (CRISPR, siRNA, knockout/knock-in models)

- Chemical probes with known selectivity profiles

- Phenotypic rescue experiments

- Biomarker modulation in disease-relevant models

From a small molecule perspective, target druggability is assessed early. Considerations include binding site accessibility, structural information availability, and feasibility of achieving selectivity with drug-like molecules.

Hit Identification

Figure 3 | Experimental and computational strategies for hit identification.

Multiple complementary approaches are used to identify initial chemical matter. High-throughput screening (HTS) enables rapid experimental evaluation of large compound libraries, while virtual screening prioritizes molecules using structure- or ligand-based computational methods. Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) identifies low-molecular-weight binders with high ligand efficiency, which are subsequently elaborated into more potent compounds. Phenotypic and natural product screening further expand accessible chemical space and biological mechanisms.

Hit identification aims to discover initial chemical matter that modulates the target with measurable activity. Hits are typically weak and unoptimized but provide a starting point for medicinal chemistry.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS)

HTS involves screening large compound libraries—often hundreds of thousands to millions of molecules—against biochemical or cell-based assays. Its strengths include:

- Broad chemical coverage

- Direct experimental readouts

- Compatibility with diverse target classes

However, HTS hits often suffer from poor drug-likeness, assay interference, or unfavorable ADMET profiles, necessitating careful triage.

DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) for Hit Identification

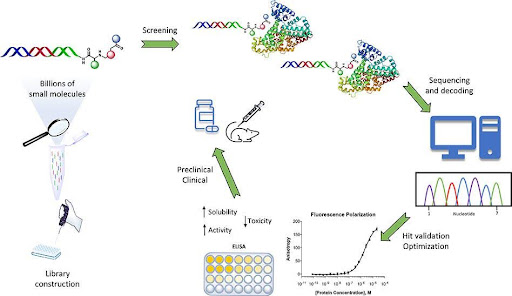

Figure 4. DNA-encoded library–based hit identification in small molecule drug discovery.

DNA-encoded libraries (DELs) consist of vast collections of small molecules individually tagged with unique DNA barcodes. Libraries are screened in pooled format against a protein target using affinity selection, followed by DNA amplification and sequencing to identify enriched binders. DEL technology enables efficient exploration of large chemical spaces but requires off-DNA resynthesis and validation to confirm binding, functional activity, and drug-like properties.

DNA-encoded libraries (DELs) have emerged as a powerful and complementary approach for hit identification in small molecule drug discovery, particularly when screening very large chemical spaces against purified protein targets. DEL technology enables the synthesis, pooling, and screening of millions to billions of small molecules in a single experiment, far exceeding the scale of traditional high-throughput screening.

Principles of DNA-Encoded Library Technology

In a DEL, each small molecule is covalently linked to a unique DNA barcode that records its synthetic history. Libraries are typically constructed using templated or split-and-pool combinatorial synthesis, where successive chemical building blocks are appended to a growing scaffold, with each step encoded by an additional DNA sequence. The result is a highly diverse collection of compounds, each physically attached to a DNA tag that serves as a molecular identifier.

Hit identification proceeds through affinity-based selection rather than functional screening. The pooled library is incubated with an immobilized or tagged protein target, allowing binders to associate while non-binders are washed away. Bound compounds are then recovered, and the DNA barcodes are amplified and sequenced to identify enriched chemical structures.

Advantages of DELs in Hit Finding

DELs offer several advantages in early-stage discovery:

- Unprecedented library size, enabling broad exploration of chemical space

- Low material consumption, as screening is performed at picomole to femtomole scale

- Rapid identification of binders through next-generation sequencing

- Efficient triaging of chemical series based on enrichment patterns

These features make DELs particularly attractive for targets that are difficult to address with conventional HTS, including proteins with shallow binding pockets or limited assay tractability.

Limitations and Design Constraints

Despite their power, DELs impose unique chemical and biological constraints that influence hit quality:

- DNA compatibility restricts reaction conditions, limiting accessible chemistries

- Binding-only readouts do not directly report functional activity

- False positives may arise from DNA–protein or linker-mediated interactions

- Resynthesis requirement, as hits must be synthesized off-DNA for validation

As a result, DEL-derived hits often require careful follow-up to confirm binding mode, potency, and functional relevance.

Integrating Drug-Likeness into DEL-Based Hit Identification

To mitigate downstream attrition, modern DEL platforms increasingly incorporate drug-likeness principles at the library design stage. This includes:

- Selecting building blocks with controlled molecular weight and lipophilicity

- Designing scaffolds compatible with Lipinski and beyond-Rule-of-Five space

- Limiting excessive polarity and rotatable bond count

- Post-selection filtering of enriched compounds using in silico ADMET models

DEL hits are typically viewed as starting points rather than lead candidates, entering the hit-to-lead phase where medicinal chemistry optimization, ADMET profiling, and structural validation are applied.

Virtual Screening and Computational Drug Discovery

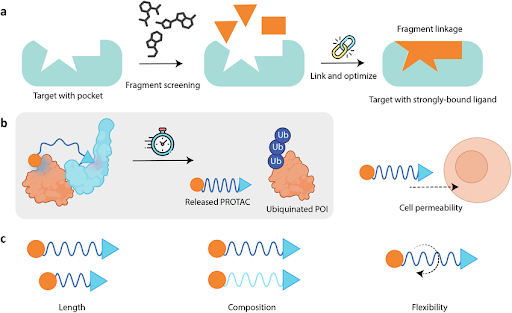

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD)

FBDD screens low-molecular-weight fragments that bind weakly but efficiently to targets. Fragments offer:

- High ligand efficiency

- Efficient exploration of chemical space

- Strong structural insights via crystallography or NMR

Fragments are subsequently grown or linked into more potent, drug-like molecules.

Phenotypic and Natural Product Screening

Hit-to-Lead: Applying Drug-Likeness Early

Hit-to-lead optimization transforms diverse hits into lead compounds with improved potency, selectivity, and basic ADMET properties.

This stage marks the first systematic application of drug-likeness principles, including:

- Molecular weight control

- Lipophilicity optimization

- Hydrogen bonding balance

- Early solubility and permeability assessment

Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR) Development

Medicinal chemists iteratively modify chemical structures to understand how changes affect biological activity. Early SAR focuses on:

- Identifying pharmacophores

- Removing liabilities (reactive groups, PAINS)

- Improving ligand efficiency

Initial ADMET Screening

Basic in vitro assays assess:

- Aqueous solubility

- Passive permeability (e.g., Caco-2, PAMPA)

- Metabolic stability in liver microsomes

- Early cytotoxicity

Compounds failing at this stage are deprioritized, reducing downstream attrition.

Lead Optimization: Balancing Potency, PK, and Safety

Figure 5 | Iterative optimization of potency, pharmacokinetics, and safety during lead optimization.

Lead optimization involves repeated cycles of compound design, synthesis, and testing to balance potency, selectivity, ADMET properties, and pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationships. Improvements in one parameter (e.g., potency or permeability) frequently introduce liabilities in others (e.g., solubility or clearance), necessitating holistic optimization strategies. Successful leads demonstrate robust efficacy, acceptable exposure, and a favorable safety margin suitable for preclinical advancement.

Lead optimization is the most resource-intensive stage of small molecule drug discovery. Here, compounds are refined to achieve a delicate balance between efficacy, exposure, and safety.

Advanced SAR and Selectivity Optimization

Comprehensive ADMET Optimization

- Solubility and permeability are optimized in tandem, recognizing their inherent trade-offs.

- Metabolic stability is improved by reducing CYP-mediated clearance and avoiding toxic metabolites.

- Distribution considerations include plasma protein binding and tissue penetration.

- Toxicity screening expands to ion channels, off-target receptors, and genotoxicity assays.

PK/PD Integration

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data are integrated to define exposure–response relationships. Successful leads demonstrate:

- Adequate bioavailability

- Predictable dose–response

- Therapeutic windows supporting clinical dosing

Preclinical Development

Preclinical development prepares a candidate for first-in-human studies. Activities include:

- In vivo efficacy studies in disease models

- Repeat-dose toxicology in multiple species

- Safety pharmacology (cardiovascular, respiratory, CNS)

- Formulation development

- IND-enabling studies and regulatory documentation

Only a small fraction of optimized leads reaches this stage, reflecting the cumulative attrition of small molecule drug discovery.

PK/PD Integration

Lipinski’s Rule of Five: Mechanistic Rationale

Lipinski’s Rule of Five emerged from empirical analysis of orally active drugs and reflects fundamental biological constraints:

- Molecular weight influences absorption and diffusion.

- Hydrogen bonding capacity affects membrane permeability.

- Lipophilicity balances solubility with membrane partitioning.

These parameters collectively approximate the requirements for passive intestinal absorption, making Ro5 a useful early heuristic rather than a rigid rule.

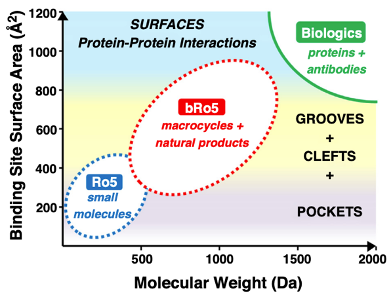

Figure 6 | Classical and expanded chemical space in small molecule drug discovery.

Lipinski’s Rule of Five defines physicochemical boundaries commonly associated with oral bioavailability, emphasizing molecular weight, lipophilicity, and hydrogen bonding capacity. Beyond Rule of Five (bRo5) compounds extend into higher molecular weight and polarity while maintaining permeability through conformational control, intramolecular hydrogen bonding, and increased three-dimensionality. These strategies enable targeting of challenging biological interfaces while preserving acceptable pharmacokinetic behavior.

Beyond the Rule of Five (bRo5)

Modern drug discovery increasingly targets challenging biological interfaces, necessitating exploration beyond classical Ro5 space. bRo5 strategies rely on:

- Conformational control and 3D shape

- Intramolecular hydrogen bonding to mask polarity

- Macrocyclization and rigidity to enhance permeability

These principles expand accessible chemical space while maintaining acceptable ADMET behavior.

Key Technologies and Methodologies Driving Small Molecule Discovery

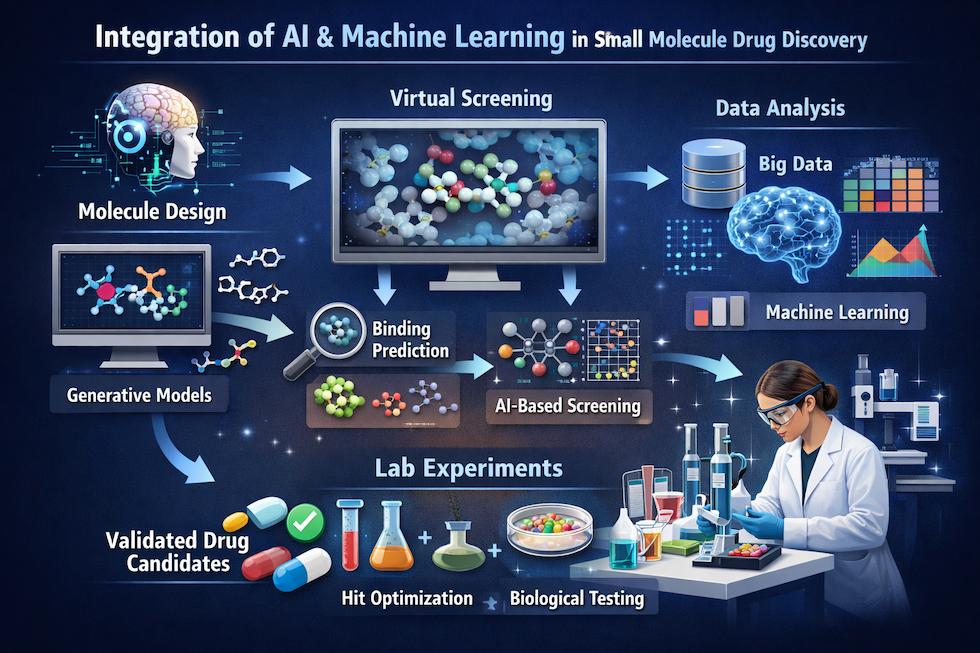

Figure 7 | Integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in small molecule drug discovery.

AI and machine learning approaches are applied throughout the discovery pipeline, from target identification using omics data to virtual screening, de novo molecular design, ADMET prediction, and retrosynthetic planning. By leveraging large chemical and biological datasets, these methods accelerate hypothesis generation, compound prioritization, and decision-making, complementing experimental and expert-driven medicinal chemistry workflows.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI and ML models are increasingly applied to:

- Target identification from omics data

- De novo molecule generation

- ADMET and toxicity prediction

- Retrosynthetic planning

While not replacing medicinal chemists, AI augments human decision-making by accelerating hypothesis generation and prioritization.

Structural Biology and Computational Chemistry

Challenges, Current Trends, and Future Directions

Small molecule drug discovery faces persistent challenges:

- Rising R&D costs and long timelines (often 10–15 years)

- High attrition rates

- Difficult targets such as protein–protein interactions

Emerging solutions include targeted protein degradation, molecular glues, drug repurposing, and personalized medicine approaches.

Conclusion

Small molecule drug discovery is a multidimensional optimization problem, requiring the seamless integration of biology, chemistry, and data science. Drug-likeness and ADMET are not static filters but dynamic design principles applied throughout the discovery pipeline. As technologies evolve and chemical space expands, small molecules will continue to play a central role in translating biological insight into effective therapies.

References

-

- Lipinski, C. A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B. W.; Feeney, P. J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 1997, 23, 3–25.

- Waring, M. J.; Arrowsmith, J.; Leach, A. R.; Leeson, P. D.; Mandrell, S.; Owen, R. M.; Pairaudeau, G.; Pennie, W. D.; Pickett, S. D.; Wang, J.; Wallace, O.; Weir, A. An Analysis of the Attrition of Drug Candidates from Four Major Pharmaceutical Companies. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2015, 14, 475–486.

- Doak, B. C.; Over, B.; Giordanetto, F.; Kihlberg, J. Oral Druggable Space beyond the Rule of 5: Insights from Drugs and Clinical Candidates. Chemical Biology 2014, 21, 1115–1142.

- Paul, S. M.; Mytelka, D. S.; Dunwiddie, C. T.; Persinger, C. C.; Munos, B. H.; Lindborg, S. R.; Schacht, A. L. How to Improve R&D Productivity: The Pharmaceutical Industry’s Grand Challenge. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 203–214.

- Hughes, J. P.; Rees, S.; Kalindjian, S. B.; Philpott, K. Principles of Early Drug Discovery. British Journal of Pharmacology 2011, 162, 1239–1249.

- Walters, W. P.; Murcko, M. A. Prediction of “Drug-Likeness”. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2002, 54, 255–271.

- Schneider, G. Automating Drug Discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 97–113.

Related Services

| Service | |

|---|---|

Small molecule drug discovery for even hard-to-drug targets – identify inhibitors, binders and modulators | |

Molecular Glue Direct | |

PPI Inhibitor Direct | |

Integral membrane proteins | |

Specificity Direct – multiplexed screening of target and anti-targets | |

Express – optimized for fast turn – around-time | |

Snap – easy, fast, and affordable |