Cancer Drug Discovery: From Breakthrough Science to the Oncology Pipeline

Table of Contents

Introduction: From Cancer Drug Discovery to Robust Drug Pipeline

Cancer is not one disease; it is a constantly evolving set of diseases driven by diverse genetic and cellular mechanisms. That complexity is exactly why Cancer Drug Discovery remains one of the most urgent and demanding frontiers in biomedical innovation: new therapies must be potent, precise, and resilient against resistance. At the same time, unprecedented advances in structural biology, computational design, and screening technologies are transforming how quickly researchers can move from biological insight to clinic-ready candidates.

The scale of the challenge is enormous. In 2022, there were ~20 million new cancer cases worldwide and ~9.7 million cancer deaths, underscoring why oncology remains one of the most urgent areas for biomedical innovation. Beyond human impact, cancer imposes a major economic burden: the total annual economic cost was estimated at US$ 1.16 trillion (2010) through healthcare expenditure and productivity loss.

In this article, we explore the modern oncology discovery-to-development continuum—from target validation and early hit finding to biomarker-driven clinical trials. We then map the major therapeutic strategies in cancer treatment, highlight recent breakthroughs shaping the small-molecule pipeline, and outline the emerging technologies poised to define the next generation of oncology medicines.

The Urgent Need for Novel Cancer Treatments

Cancer remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, and many tumors eventually develop resistance to first-line therapies. This creates a persistent need for new mechanisms, smarter combinations, and treatment strategies that can be matched to the biology of each patient.

What is Cancer Drug Discovery

Cancer drug discovery is the end-to-end scientific process of identifying actionable biological mechanisms in cancer and translating them into therapies that can safely and meaningfully benefit patients. It spans target selection, screening and hit finding, medicinal chemistry optimization, and translational strategies that connect laboratory evidence to clinical outcomes.

Its global health impact is substantial: effective oncology drug development can extend survival, improve quality of life, and in some cancers turn deadly diseases into manageable chronic conditions. Just as importantly, modern cancer drug discovery increasingly aims to match treatment to the tumor’s biology using biomarkers, enabling higher response rates and better benefit–risk balance.

A Brief History of Cancer Treatment Innovation

Early cancer therapies relied heavily on surgery and radiation, followed by the rise of cytotoxic chemotherapies that broadly targeted rapidly dividing cells. While chemotherapy delivered landmark improvements, it also revealed the limits of non-specific mechanisms especially toxicity and the tendency for tumors to recur.

The modern era introduced targeted therapies that inhibit oncogenic drivers and signaling pathways, alongside immunotherapies that engage the immune system (such as checkpoint inhibition). Today, the field continues to evolve toward tissue-agnostic approaches, rational combinations, and modalities that expand beyond classical “druggable” targets while small molecules remain central because they can reach intracellular proteins and be optimized for oral dosing.

Why Cancer is Hard to Treat and Why Discovery Must Keep Innovating

Cancer therapy is challenged by three persistent factors: resistance, toxicity, and specificity. Tumors can adapt under treatment pressure by acquiring mutations, rewiring signaling networks, or exploiting protective microenvironments, often leading to relapse even after an initial response.

At the same time, many cancer targets overlap with normal biology, creating narrow therapeutic windows and dose-limiting side effects. These realities are why innovation in cancer drug discovery matters: progress depends on better target validation, smarter molecule design, improved models that predict human response, and biomarker strategies that identify who is most likely to benefit.

From Discovery to the Clinic – What This Article Covers

This article explores how Cancer Drug Discovery is evolving, from target identification and screening through clinical testing, highlighting the therapeutic strategies shaping today’s pipelines, the technologies accelerating small-molecule design, and the future directions likely to define the next wave of oncology innovation.

The Drug Discovery and Development Pipeline

The drug discovery pipeline is long and high-risk. From early discovery through regulatory review, developing a new medicine often takes ~10–15 years and has been estimated to cost ~US$ 2.6 billion when accounting for the cost of failures. Attrition is substantial: fewer than ~12% of candidates that enter Phase I ultimately reach approval, which is why technologies that reduce cycle time and improve early decision-making are so valuable in oncology drug development.

Target Identification and Validation

Successful oncology programs start by selecting targets that are causally linked to disease and offer a viable therapeutic window. Validation typically integrates patient-derived genomics, functional perturbation (e.g., genetic knockdown/knockout), pathway biology, and translational evidence such as biomarker correlations.

In oncology, targets often fall into categories such as oncogenes (mutated or overexpressed drivers), tumor suppressor pathway dependencies, and signaling networks that control proliferation, apoptosis, and DNA repair. Common target classes include kinases and epigenetic regulators, as well as protein–protein interactions that were historically difficult to drug but are increasingly approachable through new chemotypes and modalities.

Robust validation typically requires converging evidence: patient genomics and transcriptomics, functional studies (CRISPR or RNAi perturbation), and translational biomarkers that can be measured in tumors or blood. The goal is to confirm not just biological relevance, but also a therapeutic window (evidence that modulating the target can harm tumor cells more than normal tissue).

Hit Identification and Lead Optimization

Once a target is prioritized, discovery teams identify starting “hits” using approaches such as high-throughput screening, fragment-based discovery, or DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) screening. Medicinal chemistry then refines potency, selectivity, and developability by optimizing properties like solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability while reducing liabilities.

Hit identification can begin with high-throughput screening (HTS) of large compound collections, fragment-based approaches that find small “starting pieces” for optimization, and virtual screening that prioritizes candidates computationally. DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) screening extends this reach by sampling very large chemical spaces efficiently, often revealing scaffolds not present in standard commercial libraries.

Lead optimization then iterates structure–activity relationships (SAR): chemists systematically modify the molecule to improve potency, selectivity, and mechanism-relevant properties. In parallel, teams optimize developability by addressing ADMET considerations (solubility, permeability, metabolic stability, and safety liabilities) so promising biology doesn’t fail due to poor exposure or off-target risks.

Where available, structure-guided design accelerates this loop: binding modes from crystallography or cryo-EM help identify interactions to strengthen, regions to simplify, and features that may drive selectivity. The most effective programs integrate experimental data with predictive modeling to reduce cycle time and focus synthesis on the most informative analogs.

Preclinical Development

Preclinical development focuses on building confidence that a candidate can be safely and effectively tested in humans. This includes PK/PD studies, efficacy models, toxicology, formulation work, and IND-enabling packages, ideally guided by biomarkers that can be carried into early clinical trials.

Preclinical efficacy typically starts with in vitro systems—biochemical assays, cancer cell lines, and increasingly more physiologic models such as 3D cultures and organoids paired with pharmacodynamic readouts that confirm target engagement and pathway modulation. These experiments help link mechanism to phenotype and establish biomarkers that can be tracked later in patients.

In vivo studies then evaluate exposure–response relationships, tumor growth inhibition, and tolerability in relevant models such as xenografts and patient-derived systems where appropriate. Alongside toxicology, drug–drug interaction risk, and formulation development, these data support candidate selection and IND-enabling work aimed at entering first-in-human trials with a clear mechanistic and biomarker plan.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials in oncology are typically structured in phases that balance safety, biological proof, and evidence of benefit. Phase I focuses on safety, dose and schedule selection, pharmacokinetics, and early pharmacodynamics often using biomarker readouts (e.g., pathway inhibition in tumor biopsies or circulating markers) to confirm target engagement. Early efficacy signals may be explored in expansion cohorts, particularly in biomarker-selected patients.

Phase II evaluates whether the therapy shows meaningful activity in a defined population. Common endpoints include objective response rate (ORR), duration of response, and progression-free survival (PFS), with continued safety monitoring. Many modern Phase II programs are biomarker-driven and may explore rational combinations to overcome resistance or broaden response.

Phase III tests the therapy against standard of care in larger populations to confirm clinical benefit and characterize safety at scale. Endpoints often include overall survival (OS), PFS, quality of life measures, and safety outcomes, depending on the disease setting and regulatory expectations. Increasingly, trial designs incorporate adaptive elements, stratification by biomarkers, and real-world evidence planning to strengthen the totality of data.

Across phases, oncology drug development is shaped by combination strategies, sequencing decisions, and companion diagnostics that help match treatment to the right patients. This makes translational planning how biomarkers, mechanisms, and clinical endpoints connect to success.

Regulatory Approval and Post-Market Surveillance

Regulatory approval is granted when the total evidence demonstrates an acceptable benefit–risk profile in a defined indication. Depending on disease severity and available therapies, approvals may be accelerated based on surrogate endpoints, with requirements for confirmatory studies to verify clinical benefit.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviews evidence from clinical development to determine whether a therapy’s benefits outweigh its risks for a specific indication. In Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) provides scientific evaluation that supports marketing authorization decisions across EU member states. These regulators may also grant expedited pathways (where appropriate) and require confirmatory studies when approvals rely on surrogate endpoints

After launch, post-market surveillance and real-world evidence help refine safety profiles, understand effectiveness across broader populations, and identify optimal use in combinations or earlier lines of therapy. This lifecycle approach increasingly feeds back into cancer drug discovery by revealing resistance patterns, new biomarker hypotheses, and next-generation targets.

Types of Cancer Drugs and Therapeutic Strategies

Modern cancer treatment uses multiple therapeutic strategies often in combination to attack tumors, prevent relapses, and manage resistance. While this article emphasizes the fast-growing role of small molecules, the most effective regimens increasingly blend small molecules with biologics, radiopharmaceuticals, and platform-driven approaches to patient selection.

A classic example of targeted therapy’s impact is imatinib (Gleevec), a small-molecule inhibitor designed to block the BCR-ABL kinase that drives chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Its clinical success helped establish the modern paradigm of biomarker-driven, mechanism-based oncology drug development—showing that matching a therapy to a clear oncogenic driver can dramatically improve outcomes.

Traditional Chemotherapy (Cytotoxic Agents)

Chemotherapy remains a cornerstone of cancer care, especially in combination regimens and earlier lines of therapy. These agents typically target rapidly dividing cells (for example by damaging DNA or disrupting mitosis). While effective, toxicity and limited tumor selectivity have driven the push toward more targeted, biomarker-informed approaches.

Despite limitations, chemotherapy remains essential in many regimes because it can rapidly reduce tumor burden and synergize with other mechanisms. Its constraints (systemic toxicity, variable selectivity, and resistance) are a key reason discovery efforts focus on more tumor-specific mechanisms, improved delivery strategies, and rational combinations that preserve efficacy while reducing harm.

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies work by interfering with tumor-specific dependencies such as mutant kinases, aberrant growth factor signaling, or DNA repair vulnerabilities. In small-molecule oncology drug development, kinase inhibitors have become a major class because kinases are enzymatic and often tractable for medicinal chemistry, while DNA damage response targets enable synthetic-lethal strategies in genomically defined tumors.

Targeted approaches also include biologics such as monoclonal antibodies that block receptors or ligands on the cell surface. Across modalities, the success factor is patient selection: biomarkers (mutations, fusions, amplifications, or protein expression) enrich responders and reduce unnecessary toxicity, making targeted therapies a core pillar of cancer treatment advancements. This is why targeted therapies cancer programs increasingly depend on biomarker-defined enrollment.

For example, PARP inhibitors target tumors with defects in homologous recombination DNA repair (often linked to BRCA1/2). PARP normally helps repair single-strand DNA breaks; inhibiting PARP can cause damage to accumulate and convert into lethal double-strand breaks during replication. In BRCA-deficient cells, this creates synthetic lethality—the tumor can’t compensate for the repair failure—making PARP inhibitors a cornerstone of targeted therapy in selected patients.

Immunotherapy

Checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., targeting PD-1/PD-L1 pathways) have reshaped standards of care by restoring anti-tumor immune responses in a range of cancers. Their impact has accelerated immunotherapy research broadly spawning combination strategies and next-generation agents that address non-responders and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments.

In immunotherapy, pembrolizumab (Keytruda) became one of the defining breakthroughs as a PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor, helping demonstrate how releasing immune “brakes” can produce durable responses in multiple cancers and accelerating immunotherapy research across tumor types.

Cell therapies, especially CAR T-cell therapy, represent another major immunotherapy category. CAR T has delivered profound responses in certain hematologic malignancies by engineering patient immune cells to recognize tumor antigens. The approach brings unique challenges; manufacturing complexity, toxicity risks, and antigen escape; but continues to expand through improved constructs and targets.

Ongoing immunotherapy research is expanding beyond antibodies into small-molecule immune modulation and small molecules can complement these strategies by modulating innate immune sensing, antigen presentation, or suppressive pathways within tumors. This creates an important bridge between immunotherapy and classical drug discovery pipelines, enabling combinations that may be easier to dose, distribute, and scale.

Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapies are essential for hormone-driven cancers such as many breast and prostate tumors. Small molecules play a central role from aromatase inhibitors and selective estrogen receptor degraders to androgen receptor pathway inhibitors often paired with other targeted agents as resistance mechanisms evolve.

Hormone-driven cancers often require long-term disease control strategies, which makes tolerability and resistance management especially important. Modern discovery increasingly explores next-generation receptor degraders, combination approaches with targeted agents, and biomarker-guided sequencing to delay resistance and maintain durable benefit.

Angiogenesis Inhibitors

Angiogenesis inhibitors aim to restrict tumor blood supply by targeting pathways involved in new vessel formation. By disrupting vascular support, these therapies can slow growth and may enhance the effects of other treatments in combination regimens.

However, benefit can vary by tumor type and setting, and resistance mechanisms can emerge through alternative pro-angiogenic signals. This makes patient selection, dosing strategy, and combination design critical for durable impact.

Epigenetic Modifiers

Epigenetic therapies modulate gene expression programs without altering DNA sequence, often by targeting chromatin regulators such as methyltransferases, deacetylases, or reader proteins. Because epigenetic state can influence differentiation, immune recognition, and resistance, these agents can play roles as monotherapies in select contexts or as combination partners.

In cancer drug discovery, epigenetic targets are attractive but nuanced: efficacy may depend heavily on context, and biomarkers are essential to identify responsive tumors. Newer approaches increasingly aim for higher selectivity and improved tolerability while preserving mechanism-relevant pathway control.

Emerging Therapeutic Modalities

Beyond classic categories, several modalities are rapidly reshaping oncology R&D: targeted protein degradation (e.g., PROTACs and molecular glues), epigenetic modulators, radioligand therapies, and next-generation combinations that match mechanism to biomarker. Even when the end therapy is not a small molecule, small-molecule discovery tools (screening, structure-guided design, and predictive modeling) often accelerate the path to actionable candidates.

Immuno-Oncology Drug Development

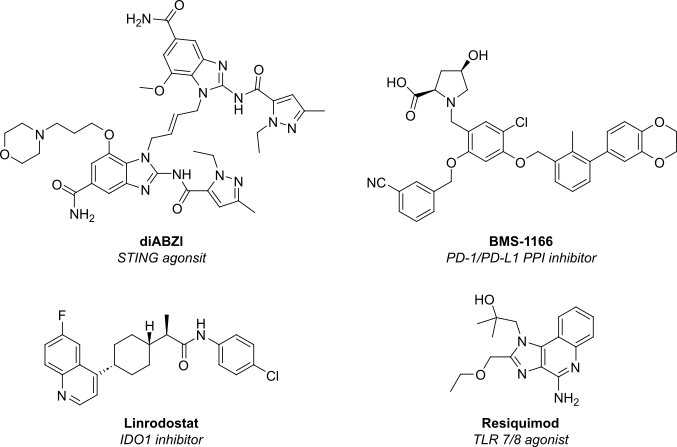

While checkpoint-blocking antibodies continue to dominate clinical headlines, a new generation of immuno oncology drugs in development are small molecules designed to modulate innate and adaptive immunity with oral or intratumoral dosing:

| Mechanism | Example of small-molecule (stage) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| STING agonist | di-ABZI (phase I) | Activate cGAS–STING pathway to boost type I IFN secretion and T-cell priming. |

| TLR7/8 agonist | BDB001 (phase II) | Intravenous TLR stimulation to inflame “cold” tumors. |

| IDO1 inhibitors | Linrodostat (phase III) | Restore tryptophan metabolism and reverse immune suppression. |

| Small-molecule PD-1/PD-L1 blockers | BMS-1166 (pre-clinical) | Oral immuno-checkpoint inhibition promises better tissue penetration. |

Figure 1: Structure of next-generation immune oncology small molecules currently undergoing clinical trials.

These approaches underscore an ongoing shift in immuno oncology drug discovery toward chemical matter that can be combined with antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, or radioligands for synergistic efficacy.

State-of-the-art Cancer Drug Design

Modern anti-cancer drug design leverages high-resolution structural biology, AI-enabled property prediction, and in-silico ADME-Tox modeling to compress timelines in the development of anticancer drugs:

High-resolution structural biology

High-resolution structural biology such as X-ray crystallography, NMR, and cryo-EM reveals how drug candidates interact with their targets at the atomic level. These structures help teams identify binding pockets, understand conformational changes, and design molecules with better fit and selectivity. In oncology, where subtle differences can determine both efficacy and toxicity, structure-guided design reduces trial-and-error cycles and supports more confident optimization decisions.

AI-enabled property prediction

AI-enabled property prediction uses data-driven models to estimate key characteristics early such as potency trends, selectivity risk, solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability before synthesizing large numbers of analogs. In practical workflows, these models help prioritize which compounds to make next, triage series that are likely to fail developability gates, and accelerate the iteration loop between design, synthesis, and testing.

In-silico ADME-Tox modeling

In-silico ADME-Tox modeling anticipates how molecules behave in the body: absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and potential toxicity. By flagging liabilities (for example, reactive metabolite risk or safety-related off-target effects) earlier in the program, teams can avoid late-stage surprises and allocate experimental work to the most promising candidates. In oncology where dosing and therapeutic windows are often tight early de-risking is especially valuable.

- Screening of millions of compounds – DEL screening allows for the identification of high-affinity compounds from a single round of screening.

- Structure-Guided Modeling – Cryo-EM structures of e.g. KRAS and RAF complexes have guided ras targeted drug development to picomolar affinity.

- Generative AI – Transformer-based models propose synthetically tractable scaffolds for “difficult” pockets (e.g. β-catenin) within days.

- Covalent fragment growing – Used to create first-in-class covalent KRAS (G12C) inhibitors, demonstrating the power of anti-cancer drug discovery that combines warhead chemistry with macromolecular insight.

- Macrocycle Design – Enables oral inhibition of allosteric mutant p53 re-activators, expanding the druggable proteome.

Collectively, these tools accelerate cancer drug design and discovery from hit identification to IND in <24 months—a milestone once reserved for antivirals.

Recent Highlights in Cancer Drug Discovery: Breakthroughs Shaping Today’s Pipeline

Cancer drug discovery is increasingly defined by biomarker-driven precision medicines, tissue-agnostic approvals, and smarter combination strategies. Below are several recent milestones that illustrate how “undruggable” targets are becoming actionable and how small molecules continue to expand what’s possible in oncology.

KRAS (G12C) – Prototype for undruggable success

- Sotorasib gained global approval for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in 2021.

- Adagrasib secured accelerated FDA approval and is under study in colorectal cancer (CRC).

Tissue-Agnostic Therapies

- The approval of Larotrectinib for NTRK-fusion tumors illustrates tissue agnostic drug development in oncology.

Hematologic Malignancies

- Venetoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor) transformed therapy for both Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) and Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) drugs in development

- Ivosidenib (IDH1 inhibitor) exemplifies targeted therapy in AML and cholangiocarcinoma

Solid-Tumor Snapshot

| Indication | Small-Molecule Class | Examples | Development Stage (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer drugs in development | FGFR2/3 inhibitors | Erdafitinib | Approved |

| Glioblastoma drugs in development | PP2A activators | NZ-8-061 | Preclinical |

| Ovarian cancer drugs in development | ATR inhibitor + PARP inhibitor | Camonsertib | Phase II |

| Lung cancer drugs in development | HER2 exon 20 inhibitors | Poziotinib | Phase II |

| Prostate cancer pipeline | CYP17-lyase and AR inhibitor | Seviteronel | Phase II |

DEL Screening: Accelerating Novel Binder Identification

DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) screening starts with libraries of small molecules where each compound is linked to a unique DNA tag that acts like a barcode. The library is incubated with a target of interest, and binders are enriched through selection steps (for example, affinity capture and washing). Researchers then amplify and sequence the DNA tags of enriched compounds, using next-generation sequencing to identify which chemotypes bind and which structures become more prevalent across selection conditions.

Because DEL can interrogate extremely large chemical spaces in a single campaign, it is particularly useful when traditional screening collections are too small or when targets are challenging. DEL screening can deliver high-quality starting points quickly, enable exploration of novel scaffolds, and accelerate the hit-to-lead stage especially when paired with structure-guided follow-up and predictive property modeling.

Key benefits for cancer target discovery and development include:

- Speed – hit emerge in weeks, shrinking the early cancer drug discovery research timeline.

- Novel chemotypes – DEL campaigns routinely identify scaffolds absent from commercial collections.

- Diverse targets – successful against E3 ligases (PROTAC starting points), kinases, proteases, epigenetic readers and more all enriching the new cancer drug discovery toolkit.

Read more about Vipergen’s DNA Encoded Libraries and Screening.

Challenges and Opportunities in Cancer Drug Discovery

Cancer drug discovery is uniquely difficult because tumors evolve under therapeutic pressure and vary dramatically between patients and even within the same tumor over time. Key challenges include identifying targets with a true therapeutic window, overcoming adaptive resistance, and translating preclinical signals into meaningful clinical benefits.

- Tumor heterogeneity and evolution: Subclones with distinct drivers can survive initial therapy and seed relapse, making durable responses harder to achieve.

- On-target toxicity and narrow windows: Many oncology targets are also relevant in normal tissue, so potency must be balanced with selectivity and exposure control.

- Resistance is the rule, not the exception: Secondary mutations, pathway rewiring, and microenvironment effects can blunt even best-in-class targeted therapies.

- Clinical complexity: Combination regimens, biomarker stratification, and adaptive trial designs are increasingly essential but raise operational and statistical challenges.

At the same time, opportunities are expanding quickly. Better patient stratification, deeper biological models, and faster discovery cycles are enabling more shots on goal – and better shots. Platforms that compress early discovery timelines and broaden chemical diversity can make the difference between a stalled hypothesis and a clinic-ready program.

Drug Resistance Mechanisms—and How to Counter Them

Drug resistance can be intrinsic (present before treatment) or acquired (emerging under selective pressure). Common mechanisms include secondary mutations in the target, activation of bypass signaling pathways, phenotypic switching, and microenvironment-driven protection that blunts immune or drug activity.

Strategies to address resistance include designing next-generation inhibitors that retain activity against resistant variants, using combination therapies that block parallel pathways, and applying biomarker monitoring to detect resistance early. In practice, resistance planning often starts during lead optimization by mapping likely escape routes and ensuring candidate selectivity and exposure profiles support combination use.

Resistance is also an opportunity: every resistance pattern teaches the field where tumors are vulnerable. These insights feed back into cancer drug discovery by revealing new targets, better combination hypotheses, and clearer patient-selection strategies.

Toxicity and Side Effect Management

Oncology drugs often operate near the limits of tolerability, especially when targets intersect with normal cell biology. Toxicity management begins in discovery with selectivity profiling and early liability screening, and continues through dosing strategy, formulation, and careful combination design to avoid overlapping adverse effects.

Biomarkers can help here too by enabling lower effective doses in responsive patients and guiding treatment interruption or sequencing. The goal is to maximize time on therapy and preserve quality of life without sacrificing efficacy.

The High Cost of Drug Development

Cancer drug development is expensive due to long timelines, complex trials, manufacturing requirements, and high attrition rates. Biomarker-driven enrollment and more predictive preclinical models can reduce failure risk, but they also introduce additional operational costs and coordination across diagnostics, sites, and regulators.

This makes efficiency-critical platforms valuable: faster hit finding, better early de-risking, and compressed optimization cycles can materially reduce total program cost and increase the probability of reaching decisive clinical proof.

Drug Repurposing as an Opportunity

Drug repurposing (finding new oncology uses for existing medicines) can shorten timelines because safety and manufacturing knowledge already exist. Repurposing can be especially attractive when a known mechanism aligns with a newly discovered biomarker-defined subgroup or when combination logic suggests benefit in a new setting.

While repurposed drugs may not always deliver the potency or selectivity of a purpose-built oncology agent, they can create rapid clinical hypotheses, inform next-generation design, and provide near-term options where unmet need is high.

Future Directions in Cancer Treatment

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Drug Discovery

AI is increasingly used to prioritize targets, design molecules, predict properties, and suggest synthetically tractable series. When integrated with experimental feedback loops, AI can reduce cycle times in medicinal chemistry and help teams focus resources on candidates with a higher probability of success.

Beyond property prediction, AI and machine learning can strengthen decision-making across the drug discovery pipeline—from target prioritization to hypothesis generation and compound design. Models trained on omics data and literature-derived knowledge graphs can suggest target–disease links, propose combination hypotheses, and identify patient segments most likely to benefit.

In chemistry, generative approaches can propose novel scaffolds optimized for multiple objectives (potency, selectivity, ADMET, and synthetic accessibility). When paired with rapid experimental feedback (screening, structural data, and translational biomarkers) AI becomes most valuable as a cycle-time compressor, helping teams learn faster and avoid unproductive design paths.

Precision Medicine and Personalized Oncology

Precision oncology is shifting drug development from broad tumor labels to biomarker-defined subpopulations. As diagnostics improve, discovery programs can be designed with patient selection in mind from the start, hereby improving signal detection in trials and enabling rational combinations tailored to resistance mechanisms.

Precision medicine depends on biomarkers that reflect tumor biology such as mutations, fusions, protein expression, or functional signatures and on diagnostics that can reliably measure them. In practice, this enables oncology drug development to move from broad populations to biomarker-defined cohorts where the probability of response is higher and clinical trials can read out more clearly.

Personalized oncology also increasingly incorporates longitudinal monitoring, such as blood-based biomarkers, to track disease dynamics and resistance emergence. This can inform treatment switching, combination timing, and next-generation drug design aimed at known resistance mechanisms, hereby tightening the feedback loop between the clinic and cancer drug discovery.

CRISPR and Gene Editing

Gene-editing tools accelerate target validation and mechanism-of-action studies by enabling rapid functional testing in relevant cellular systems. While therapeutic gene editing is not the focus of small-molecule pipelines, CRISPR-driven biology can substantially improve confidence in discovery and uncover synthetic lethal relationships that small molecules can exploit.

Large-scale CRISPR screens can map genetic dependencies and synthetic lethal interactions, revealing vulnerabilities that small molecules can exploit. These tools also help deconvolute mechanism-of-action, validate combination partners, and prioritize targets with stronger causal evidence—reducing translational risk before substantial chemistry investment.

Organoids and Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX)

Advanced models such as tumor organoids and patient-derived xenografts (PDX) can better preserve tumor heterogeneity and clinically relevant response patterns than traditional cell lines. They can improve confidence in whether a mechanism translates to complex tumor biology and can be used to test biomarker hypotheses earlier.

While no model is perfect, these systems are valuable for ranking candidates, evaluating combination strategies, and exploring resistance. Used thoughtfully, they strengthen the bridge between discovery results and clinical trial design.

Combination Therapies

Combination therapies are increasingly central because many tumors activate alternative pathways or adaptive responses when a single driver is inhibited. Rational combinations can deepen response, delay resistance, and expand benefit to broader patient groups, especially when grounded in mechanistic understanding and biomarker strategy.

For drug discovery teams, combinations influence everything from screening and model selection to safety planning and clinical endpoints. The best programs design combination logic early (e.g. identifying complementary mechanisms and anticipating overlapping toxicities) so the clinical strategy is not an afterthought.

Conclusion: The Future of Cancer Drug Discovery

Cancer drug discovery is moving faster—and becoming more precise—through the convergence of biomarker-driven development, structure-guided design, AI-enabled prediction, and screening platforms that expand accessible chemical space. At the same time, oncology pipelines are increasingly shaped by tissue-agnostic strategies, rational combinations, and small molecules that complement biologics and emerging modalities.

As these trends accelerate, success will favor teams that can connect discovery and translation seamlessly: validating targets with confidence, generating differentiated starting points quickly, and optimizing molecules with developability in mind. Vipergen supports this shift by enabling rapid, scalable discovery workflows—particularly through DNA-Encoded Library screening strategies that help identify novel binders and unlock new medicinal chemistry starting points.

FAQ

Cancer drug discovery is the process of identifying tumor vulnerabilities and turning them into therapies through target validation, screening, medicinal chemistry optimization, and translation into clinical testing.

It often takes many years because candidates must progress through discovery, preclinical testing, and multiple clinical trial phases before regulatory review. Timelines vary widely depending on mechanism, biomarker strategy, and trial complexity.

Key References

- Bray, F. et. al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries, CA Cancer J. Clin., 2024, 74 (3), 229-263. doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834

- Drilon, A. et. al. Efficacy of Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion-Positive Cancers in Adults and Children., N. Engl. J. Med., 2018, 378, 731-739. doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1714448

- Kamb, A., Wee, S., Lengauer, L. Why is cancer drug discovery so difficult? Nat. Rew. Drug Discov., 2007, 6, 115-120. doi.org/10.1038/nrd2155

- Hochhaus, A. et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, N. Eng. J. Med., 2017, 376, 917-927. doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1609324

- Lyou, Y. et. al. Infigratinib in Early-Line and Salvage Therapy for FGFR3-Altered Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma, Clin. Genitourin. Cancer, 2022, 20 (1), 35-42. doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2021.10.004

- Helleday, T. The underlying mechanism for the PARP and BRCA synthetic lethality: Clearing up the misunderstandings, Mol. Oncol., 2011, 22, 5 (4), 387-393. doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2011.07.001

- Qiu, X. et. al. Advances in AI for Protein Structure Prediction: Implications for Cancer Drug Discovery and Development, Biomolecules, 2024, 14 (3), 339. doi.org/10.3390/biom14030339

- Skoulidis, F. et. al. Sotorasib for Lung Cancers with KRAS p.G12C Mutation, N. Engl. J. Med., 2021, 384, 2371-2381. doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2103695

- Yap, T. A. et. al. Camonsertib in DNA damage response-deficient advanced solid tumors: phase 1 trial results, Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1400-1411. doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02399-0